Linkbar

Showing posts with label l'arte dei rumori. Show all posts

Showing posts with label l'arte dei rumori. Show all posts

07 September 2017

Because

Honestly, back in the days when Julian Cope's Krautrocksampler doc became the Young Person's Guide to Same, I took issue with the author's assertion that German prog was part of a concerted effort to shed all all Anglo-American influences. True enough if you're listening to Neu!, Harmonia, Kraftwerk, Cluster, and Faust; but not much of the case at all when applied to most of their German prog contemporaries.

And not so true much early Can, either; which -- despite however adventurous it aiming to be -- still adhered to the arc set by Anglo-American psych/blues/"freak-out" models. But that would change soon enough , all such stuff was gradually stripped away and the music pared back to its base elements. Which is probably why Ege Bamyasi and Future Days remain the albums I most often revisit. With the former album, the band starts to shed the aforementioned baggage -- with Czukay's bass and Jaki Liebezeit's drums brought prominently into the foreground, guiding much of what transpires, mixed and crafted in a way that created an uncanny sense of sonic spatiality. The latter album followed further down that path -- far enough to achieve its own peculiar musical universe.

It was heartening to see Czukay paid proper tribute when the post-rave electronic music boom of the late 1990s came along -- his contributions as an e-musik pioneer widely recognized, thus giving him a second life with a new generation of listeners. I recall clips of him playing as festivals, bobbing and dancing around behind racks of new-gen gear, delighted that the world still kept offering him the means to further explore musical ideas that had gotten into his head from his early days as a Stockhausen student.

28 November 2016

The Day I Disconnected The Erase Head And Forgot To Reconnect It

I suppose by this point I should quit occasionally popping up to say "please pardon my absence," as I've been doing more often than anything else (here) in many months. But I only recently discovered that this blog had been knocked out by a tech glitch. It seems google did some sort of update and the tweaking rendered some html meta-tag coding on the blog's template unparsable, thus taking this thing off the air. Which has since been remedied.

At any rate, a belated RIP is in order for e-music pioneer extraordinaire Pauline Oliveros. Admittedly, I don't own nearly enough of her work (although, if I had the money to spare, I imagine this collection from a few years back would've done nicely). But back when I used to do the free-mixing session for an experimental music radio show that aired late in the Chicago p.m. , what I did have of her work often filled the bill for providing one element or another to an hour-long multilayered mix.

So, with that in mind, here (link below) is one such mix that dates back to about a decade ago, with Oliveros taking the lead...

Flotsam on the Ocean of Sound (Radio mix no. 12)

Primary material includes:

Pauline Oliveros - “Something Else” (Pogus)

Brutum Fulmen - “Spore” (Crippled Intellect)

Miko Vaino - “Vaihtuja” (Wavetrap)

Robert Normandeau - “Tangram” (Empreintes Digitalis)

John Wall - “Construction III” (Utterpsalm)

Joji Yuasa - “Projection Esemplastic for White Noise” (Neuma)

Douglas Quin - “Canada Glacier/Wind Harps of Taylor Valley" (Miramar)

Merzbow - “Tatara" (Manifold)

Pimmon - “Bettler Kempt” (Fat Cat)

Stillupsteypa - “Nice Things to File Away Forever” (Mille Plateaux)

15 October 2014

Objets sonore, II

Not every electronic composer can boast of having learned his chops while editing and composing for "Tom & Jerry" cartoons.

Re, as with what I stated earlier about Richard Maxfield. It seems like saying that the music of Tod Dockstader has been unfairly neglected or undocumented is akin to sending the USS Cliché to run aground on the Shores of Redundancy. At least in Dockstaer’s case, there’s actually a few discs of the collected early work, plus that spate of recent productivity that was released about a decade ago, executed shortly before his faculties started to sadly decline.

Watching the clip from the proposed documentary above, I can’t help but be struck by how Dockstader seems so much as he did in that series of b&w photographs taken in 1966, during the recording sessions for Omniphony. A tall figure towering over the equipment, the hairless head gleaming under the overheard lights, and - in many of the images - some sort of smile across his mug, as if there were nothing else in the world he’d rather be doing than pushing sounds around, exploring new sonic syntaxes. One can’t help but wondering if his early jobbing as a film editor didn’t have something to do with why it is his pieces - when stacked alongside those of his then-contemporaries - moved with such brisk fluidity.

From an interview with Chris Cutler, c. 1993:

"I'd done quite a lot of music in a relatively short time. I'd almost lived in that studio for six, seven years, engineering by day and doing my music in down-time, nights, and weekends there. Concrete and electronic music was an expensive music to make, then; it cost a lot in time and money - too much money, in those days, for some one working alone. And time... l was pushing those studio machines hard, and they were always breaking down and I had to stop and fix them right then, no waiting, so they'd be ready the next working day. A regular composer, what's the worst will happen? He breaks a pencil, he loses a few seconds. l break a big Ampex and you lose most of a day, or, in my case, your job if you can't get it working again. And the heat... The decks would get so hot you couldn't touch them and you'd have to turn them off to cool down for a while. It really was like a kitchen. I read, much later, where someone from those days - maybe Berio - said he couldn't believe he put in all that physical work that tape-music demanded. Of course, he had another way to make music: he went back to writing, as Stockhausen and most others did around that time, late 'Sixties, 'Seventies. I suspect many of them turned away with a sigh of relief. But, as I've said, I wanted to make music out of sound, not the other way around, even if I could have. And then, things were changing even while I was still at it. The 'Glorious Junkshop,' as someone called it, of [musique] concrète was closing. And it did."

And at a later point in the same interview:

"TD: I remember I got a couple of 'phone calls in the 'Eighties from someone, I don't remember his name, who said he was working in a group, composing, or trying to, and they were all listening to my LPs, and could I tell him what to do. I didn't know what to say to him, except, don't worry it, just do it. Because, I'd always worked alone, not even listening to other people's music then, let alone working in a group. So, what were they hearing in my music? I don't know; maybe - it's the hands.I'm not so sure about the doco. But at the very least, maybe there should be a Kickstarter campaign to liberate and market the musical contents of Dockstader's hard drive.

CC: 'Hands'?

TD: Well - in painting, which I studied, seriously, in school, we used to say a painter we liked had 'good hands.' You could see his hand in the work, in the brush-work. This was early 'Fifties, with painters like DeKooning and Bacon; they had great hands. And, for me, like painting, making music was always a very physical thing, very tactile. I played those tape machines like a DJ plays turntables, rocking reels back and forth, pulling the tape through by hand. The only time I sat down was to edit - more hand-work - otherwise I was always in motion. ..."

22 December 2013

When Was Futurism?, Slight Return

More about the history of electronic music in Russia:

"Arseny Avraamov, however, planned to destroy pianos on a much more dramatic scale than Liszt. Avraamov reviled the piano because he thought that the traditional Western musical scale was irrational and even harmful. By restricting themselves to only twelve pitches out of a whole continuum of possible frequencies, Avraamov believed that musicians had dulled the perceptual capabilities of entire populations, preventing them from fulfilling their human potential. After the October Revolution, he made a proposal to Anatoly Lunarcharsky, the Commissar of Public Enlightenment, that all pianos in the country should be gathered up and burned. The proposal was fortunately unsuccessful, but Avraamov did go on to conduct extensive research on novel possibilities for microtonal music, devising his own 'Ultrachromatic' tone system and inventing instruments to perform it."

At n+1, Colin McSwiggen reviews the recent title Sound in Z: Experiments in Sound and Electronic Music in Early 20th Century Russia by Andrey Smirnov, a book that developed out of the research Smirnov conducted for the 2008 exhibition of the same name.

The site 99% Invisible posted an article about Avraamov's famed "Symphony of Sirens" this past May. Preservation Sound has a few words to say about the book, as well; mostly concetrationg of Avraamov and Evgeny Sholpo's hand-painted graphic scores. More about all of this cane be found at the the site 120 Years of Electronic Music, which lately has been making heavy use Smirnov's book as primary source for various articles on the topic.

See also Miguel Molina Alarcón 2008 publication Symphony of Sirens, via Monoskop.

Labels:

electronic music,

l'arte dei rumori

0

comments

06 December 2013

When Was Futurism?

Curious. First I've heard of it, and very intrigued. Apparently out -- in Austria, at least -- since this past April, having also been screened at this year's Mutek Festival held in Mexico City.

A write-up of the film at The Hollywood Reporter describes the span and focus of the film, highlighting the peculiar and esoteric development of Russian electronic music history, which evolved by its own logic and means, mainly due to its isolation from the rest of the world during the many decades of the Soviet era. Which would explain why many Russians at the time may never have heard of the work of, say, David Tudor or Otto Luening; which is also why many of us elsewhere probably know little of Russian electronic music beyond Léon Theremin or Eduard Artemiev.

But I do recall hearing some electronic music from Russia back just shortly before the turn of the millennium. Back around that time, I was listening to a lot of experimental electronic and IDM-type fare, recording by a slew of emerging artists who very much in the thrall of Autechre-esque sound-twisting and sonic abstraction. Eventually you began to see similar artists of that type popping up in non-English-speaking countries. Amongst the lot, roughly around 1999, were a number of Russian acts whose music began circulate via compilations or the odd European release.

I was probably among a small number of people of people took much notice at the time. In some way, I was a little fascinated by it. Something about this type of experimental music transcending borders, language barriers, and cultural peculiarities; being taken up and created by musicians in a variety of countries. In a way, it was almost like the spread of certain types of abstract art & design in the early portion of the 20th century -- post-Kandinsky modes of "pure abstraction" in painting, or intentionally international styles like those connected with the Bauhaus or De Stijl schools. Or so I would've liked to have thought.

At any rate, here's a few I remember...

03 December 2013

22 November 2013

Because

RIP Bernard Parmegiani.

Simon has some words, as well as a relay of those by Keith Fullerton Whitman. Simon also has a playlist that features many pieces that I also would have selected. To which I might only add checking out De Natura Sonorum in full, if you don't know it already. And then there's this recent clip of his Violostories, as performed live at V22 by Aisha Orazbayeva.

Labels:

acousmata,

electronic music,

l'arte dei rumori,

music,

RIPs

2

comments

17 February 2013

L'opera abbandonatta (Dead frequency broadcast no. 01)

Recently going through some archives, for the sake of cd-r salvaging and transference. Recordings of some mix sessions I did about 7 year or so ago, when -- one among other radio shows I did on a local community station in Chicago -- I was one of the hosts of an experimental music/"avant"/"noise" type program.

What this is, or was, was me in the studio booth between the dark hours of midnight and 1 A.M., in a slot that had been allotted for sending such stuff over the airwaves. So after two hours of standard-format hosting complete with the usual blahblah, we had that third of hour of sponsor-/PSA-free midnight programming to mix straight through for an hour, making use of the studio's gear as we saw fit. If the station's engineer had done his job properly -- which was infrequent, because they were usually in arrears on paying him -- we had 3 turntables, 3 CD players, 2 tapedecks, and a DAT to work with (plus means for patching a laptop in, if you disabled one of the tapedecks). And of course the multi-channel mixing board. I did a lot of these shows, co-hosting on an alternating schedule with a local noisician of note who worked wonders during the slot in question.

Several "classic" or obvious choices in this edition. I think my point at the time was to challenge myself, to use a fair amount of material that for various reasons didn't "work" in the sort of mixes I was doing; that was too "difficult" -- either too "thin" or too sporadically busy or whatever -- to easily lend itself to the way I was mixing with the studio's soundboard and equipment. This explains the use of Varèse and Gilmetti and about half of the things in the selection. The intent being to try and make it work via remixing -- mostly by ay of some real-time manipulation of the material, but also heavily supplemented with some processed loops and excerpts that I'd prepared and burned in advance. Originally, I was midly content with the results of this one; but going back and listening to it again after a long time, I think it sounds better than I thought. Maybe not one of the best I did, but not at all fucking bad, in the end.

This being a real-time "radio event" or whatever type thing, recommended conditions would be: Late-night listening, preferably with headphones. So have at it, if you're so inclined.

::: dwnld ::::

semi-complete tracklist:

◼ vid / 'forever in your infinite clutch' / phthalo / 2001

◼ edgard varèse / 'poème électronique [rmxd]' / columbia / 1972

◼ vid / 'genome illustration' / phthalo / 2001

◼ holger czukay / 'boat woman song [rmxd]' / spoon / 1982

◼ vittorio gelmetti / 'l'opera abbandonatta... [rmxd]' / nepless / 1997

◼ walter ruttmann / 'weekend: dj spooky remix' / intermedium / 2001

◼ einstürdzende neubauten / 'wasserturm' / pvc / 1984

◼ liminal / 'before and after' / knitting factory / 1995

◼ philip jeck / 'vinyl coda i' / intermedium / 2000

◼ sub dub / 'babylon unite ii' / the agriculture / 2001

◼ m singe / 'untitled, live @ cultural alchemy' / soundlab / 1999

◼ christian marclay / 'dust breeding' / atavistic / 1997

◼ morphogenesis / 'live @ shepherd's bush empire' / paradigm / 2001

◼ michael prime / 'hallucinations of falling' / digital narcis / 1999

◼ christian marclay, dj olive & toshio kajiwara / 'live in detroit, 2002' / asphodel / 2004

◼ richard h. kirk / 'synesthesia' / grey area / 1992

◼ steve roden : in be tween noise / 'the radio' / sonoris / 1999

◼ 310 / 'on the lamb' / 310 / 1997

04 December 2012

IV

After a some years had passed and with the benefit of hindsight, it was unanimously agreed that it was an early and significant salvo in what would become a never-ending war against "twee."

Labels:

art,

l'arte dei rumori,

misc.,

we're into movements

0

comments

05 November 2012

Without Erasing: The Missing Music of Richard Maxfield

Writing in his book Ocean of Sound some years ago, David Toop observed: "If Richard Maxfield had not committed suicide in 1969, and if his electronic music pieces were not so difficult to find or to hear, then our idea of how music has changed and opened out during the past thirty-five years might be very different." Toop penned those remarks back in 1994; and, even at this much later date, the thought still holds true. Before jumping to his death from a hotel window ledge in Los Angeles at the age of 42, Maxfield could be considered one the chief pioneers of electronic music on American shores.

Despite the archival cornucopia that it offers, Reissue Culture has had its share of oversights, and Maxfield has been one of them. Only a few of his compositions have seen digital reissue over the years, with works like the three-minute "Amazing Grace" or 1963's "Pastoral Symphony" turning up on a few scattered compilations. Depending on which account you go with, when he left New York for the West Coast, Maxfield entrusted his tapes to artists Walter De Maria; who passed them along to La Monte Young, who in turn reputedly entrusted them to the Dia Arts Foundation.

Terry Riley, being interviewed in the course of a game of "Invisible Jukebox" in The Wire back in 1999 shed some light on Maxfield's neglected legacy. Maxfield, he asserted, was one of the most brilliant yechnicians in American electronic music. Aside from reputedly having built much of his own equipment, Maxfield was also reputedly something of a wizard at tape-splicing -- stoically patient, exacting and precise when it came to the task of taking things apart and putting them together viz the yarns and reels of magnetic tape. La Monte Young similarly testified to the artist's skills:

"He was an incredible electronic music teacher and master engineer. I used to go up to his mixing studio when he worked at Westminster Records in 1960-61 and observe him editing those old reel-to-reel tapes. He was the most amazingly adept tape handler I have ever seen. He worked so fast his hands and the tape were a constant blur... He really understood electronics; he was very creative and experimental. He taught electronics and composition at the highest level."

Much of Maxfield's technical expertise came from his workaday duties for the classical music division of CBS Records. Aside from tightening up the performances of various symphonies and the like, this also routinely meant cutting out whatever intrusive noises might've issued from the audience that night, such as the interludinal coughs and throat-clearings from season ticket holders. One piece Riley spoke of in the interview was "Cough Music," in which Maxfield took these extracts (from the performance of a Christian Wolff piece) from the cutting-room floor and spliced them together in the order his choosing, subjecting the sounds to varying degrees of processing and manipulation. I'd long been curious about this piece, and was only recently finally able to hear it...

In the same Wire piece, Terry Riley also said of Maxfield:

"He had a fantastic ear for different kinds of sounds, just using sine wave generators he did great work. Later he did a lot more concrète stuff; one year he brought this piece out to play called 'Dishes.' He was washing dishes one night and turned his tape recorder on, so he was making found object pieces, too."

Which I suppose makes his a precursor to concrète-variety "microhouse" in a way, anticipating Matthew Herbert's Around the House by some thirty-plus years. But Richard Maxfield released only a handful of recordings during his lifetime, and only a few have been reissued over the intervening years.

A few years after having read about Maxfield's work, I acquired this item, done as a one-off, sampling-based collaborative project by a trio of East Coast electronic doodlers, released in 2002 via the Pittsburgh-based Kracfive label. It went largely unnoticed at the time, by I liked the album very much. One track in particular grabbed my interest, making me wonder if it wasn't conceived as a tribute to Maxfield's "Cough Music" by way of Kraftwerk's "Tour de France"...

Occasionally mid-grade mp3 bootleg collections of Richard Maxfield's known recorded works have appeared on the internet in recent years. Just how what and how many works Maxfield composed and committed to tape is mainly a matter of conjecture. Some compositions exist only in the form of rumor and anecdote, the recollections of his colleagues. This webpage offers what's thought to be a comprehensive inventory; but as the frequent appearance of blanks and question marks indicate, the accounting involves a fair amount of guesswork. Of these, one wonders how many have survived -- considering the shelf-life of magnetic tape and its rate of disintegration. At some point, one figures, a multi-disc anthology of the composer's work -- complete with an accompanying book on his life, work, influence on and contributions to the formative years of electronic music in the United States -- might've already seen the light of day.

And on a related note: Continuo bids farewell. But last time I checked, there was no similar cross-post on Continuo's Documents tumblr as of this morning.

10 October 2012

Objets sonore

Confluential cross-posting. I stumbled upon this clip last week and been meaning to post it. And Simon pops up with a posting of the a related BBC 1979 program, "The New Sound of Music," which I happened across at the same time as the above.

Simon points out that BBC Radiophonic Workshop is about to be relaunched. According to a statement by Matthew Herbert, who's now the Workshop's Creative Director:

"Instead of being confined to rooms full of equipment in Maida Vale studios in London, the new radiophonic workshop will instead be a virtual institution, visibly manifested as an online portal and forum for discussion around the challenges of creating new sounds in a world saturated in innovative music technology but lacklustre in terms of actual original output. we will primarily bring together two key disciplines: music composition and software design and as such its members will be drawn from the cutting edge of both."

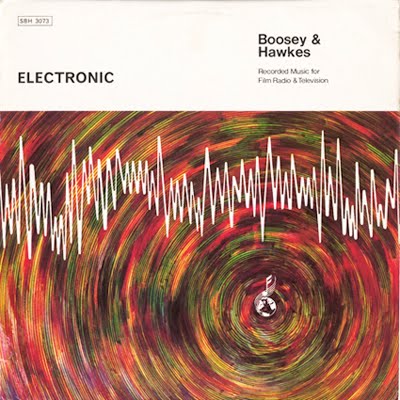

Between that and Mordant Music's current reissues of two LPs of library music by Tod Dockstader (originally done for the music publishing firm Boosey & Hawkes back in 1979-81), it looks like previously elusive histories and legacies are perpetually being maintained and rediscovered.

27 July 2012

Face the Windmills, Turn Left

Once again, a belatedly acknowledged passing...

"My father (whom I have never known as I was barely one year old when he died) had wanted me to grow up with music. There was a phonograph in our house and a number of records. Those were my only toys. Records of opera arias, operetta tunes, classical pieces, among others. I was also hearing music that the environment was offering me, music that I regarded rather anodyne and I began to say to myself that there ought to be more to music than all that. Indeed there was."

^ ^ ^

"My interest in electronic music was reactivated when...a couple of discs arrived from France. They contained the initial compositions of what we termed musique concrète: works by Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry. A new epoch in music history had begun, I thought, one that could even be regarded as the beginning of music history proper, all that preceded being only a sort of pre-history. We were in the early '50s and I was in Ankara, Turkey. Lacking proper tools, I couldn't do whatever I would have wanted to do in this new field. Later I learned that with improper tools, too, one could compose electronic music but, by then, I had only the proper tools."

^ ^ ^

"Applying to the INS some years ago, for a Re-Entry Permit. Form completed, I handed the man in charge a 20-dollar bill required as application fee. He gave me a suspicious look and said, 'On the application it says Profession: Composer. If you're a composer, how come you have 20 dollars in your pocket?'"

^ ^ ^

"My association with the Columbia Princeton Electronic Music Center ended in 1989... The reason for the termination: smoking was prohibited in all areas of the building. Some years later...the equipment of the 'classical' studio -- tape recorders and all -- was discarded, replaced by computers, which would have terminated my association anyway."

^ ^ ^

"Occasionally Ussachevsky would ask me at the last minute to take over the electronic music class. I would be totally unprepared, so I would start my address by asking, 'Any questions?' and proceed from there."

^ ^ ^

"During my earliest days of in the electronic music studio, I became aware of a parallel between the tools and the process of filmmaking and those of composing electronic music (on tape). Often I am asked how I composed this or that piece of electronic music, and as often my answer refers to a cartoon I saw somewhere, some years ago. The first expedition to Mars returns and journalists are eager to know all about it. Says the chief of the expedition: 'We were all so full of wonder that we forgot to take notes.'"

excerpts from an untitled autobiography, by İlhan Mimaroğlu.

Printed in Bananafish, issue 13, c. 1999

Labels:

acousmata,

electronic music,

l'arte dei rumori,

RIPs

0

comments

17 July 2012

A Measured Existence

One weird experience of the the past year has been watching an artist that I followed closely, and always been fascinated with, for almost three decades sort of majorly blow up in the artworld. And by the artworld, I mean the visual artworld, whereas the artist in question previously was a huge figure in the experimental music/sound art end of things, and something of a peripheral figure as far as the rest of all such art realms were concerned.

I'm talking about Christian Marclay, and the surprising unanimous accolades that he's received for his 24-hour video installation piece "The Clock," which was a huge award-winning success at the Venice Biennale back last June. The project having been a laborious effort for Marclay -- "ambitious" as they say, involving about 3 full years of intricate effort, with Marclay sinking deeply into a medium that he'd previously only dabbled with on and off over the years. I mention it, because the New Yorker had a long article about Marclay and "The Clock" some months ago, which went into a great deal of detail about the making of the piece, and (to my surprise) they made the whole thing available online. So, for the interested...there you have it.

While we're at it, here's his "Stop Talk" piece that he did back in 1990 for New American Radio. It's still available for download, though I should warn that the file's in Real Audio format, which might pose a problem if you don't have an Real player or a means to open/convert the file. But if that isn't a issue, while you're at it poke around at some of the other contributions in the NAR archives. An item of interest for some might be the entries from Don Joyce and Negativland; one of which is what amounts to an epic extended director's cut of "Guns!".

Labels:

acousmata,

art,

audio culture,

l'arte dei rumori,

salvagecore

4

comments

27 March 2012

This is Entertainment, Part III

|

| Die kinder sind in ordnung: Einstürzende Neubauten, anticipating the future of industrial music |

Phil popped up the comments last time around offering that TG constituted a sonic "Year Zero -- a band who were previously unthinkable." True enough, I suppose. Returning to Simon's remarks about the psychedelic underpinnings of early industrial music, I tend to see it as an inversion of an aesthetic, of what had constituted music-making a decade prior. That being that it constituted a centering on the other end of the process -- focusing on the blurred and distorted sound-for-its-own-sake segues and embellishments that were such a part of psychedelia, so often the product of the (electro-acoustic) studio-as-instrument method of crafting sound, and expanding it out into an entire sonic pursuit.1

Or that's the way it started out, anyway. Up to that point, the industrial moniker had remained fairly open and vaguely descriptive -- referring to little more than a loose and dirty approach to electronic sound and tape collage. But by the early-mid 1980s it had begun to ossify into a descriptive term for the trademark sound of a particular subgenre. It's at this point – with the emergence of Einstürzende Neubauten and later Test Department, each offering up the din of scraped and pummeled metal on metal -- that one began to sense that the industrial label was being explored a tad too literally; and that in the process the whole enterprise was drifting into more limited (if not self-limiting) territory.

And then there was the model offered SPK's Machine Age Voodooo, which in the end proved to be the biggest harbinger of things to come. For anyone who had taken an interest in industrial music, the middle 1980s offered two alternatives. The first was to follow the newly emergent rhythmic/pop developments into the realm of the burgeoning "industrial dance" scene, or burrow further into the amusical sonic abstraction. The second could be accessed by way of the then-proliferating first-gen cassette underground -- the domain of low-budget electro-acoustic "noise music" of the Merzbow/RRRecords variety. As far as such stuff was concerned, the first option didn't hold much appeal for me at the time, so I ended up going with the latter.

At any rate. Inasmuch as the Cabs zag into "urban" terrain might've constituted a radical deviation from their earlier material, it wasn't altogether unsurprising. There'd long been funk underpinnings in their music in the years leading up to stint on the Virgin label. And of course there was the pervasive post-punk flirtation -- for reasons both aesthetic and political -- with disco, funk, and hip-hop. Add to that the existent cross-pollination occurring between the music centers of New York and London, with acts like the Clash, A Certain Ratio, and New Order having already courted the NYC post-disco dancefloor set, not to mention Grace Jones covering tunes by the likes of Joy Division and The Normal.2

24 March 2012

Blame it on Varèse

The first clip brings to mind the second. Which in turn prompts me to remember Zbigniew Rybczyński, the Polish filmmaker and cinematographer who was a pretty in-demand video director for a brief spell in the mid '80s after doing the Art of Noise joint -- briefly hot property for his ability to make videos that left a lasting impression and endowed the product with some quirky artiness or whatever. Around the same time he did this one and this one, which I remember thinking quite amusing at the time, but weren't quite so successful in putting the product over. And as I recall, he was also this one, which needed at least three times as many extras and an infinitely better band to achieve the desired effect.

But anyway, I was never sure about what the Monkees-Zappa connection was; except for maybe the flimsy coincidence that Nesmith and Zappa both seemed to share the same scoffing derision for the drug culture of the era(?).

Labels:

l'arte dei rumori

0

comments

23 March 2012

This is Entertainment, Pt. II

Drew Daniels, in his 33 1/3 guide to 20 Jazz Funk Greats, writing about Throbbing Gristle in the final stretch of their first incarnation:

"The aesthetic deathgrip of such Grand Guignol fare initially helped to cast a suitably threatening media shadow, amplifying the already plentiful notoriety of Coum's alumni as nihilistic perverts and 'wreckers of civilization.' But it ultimately proved stifling and tedious to the members of the band, who had to watch as their antihumanist gestures were photocopied and distorted endlessly by arrivistes who brought plenty of iron-stomached bloodlust but forgot to pack the critical savoir faire. ...The effects of such associations proved more damaging and longlasting than the band predicted."

Damaging and stifling perhaps, but the crucial term in this context might be when Daniels reaches for the word tedious. Because I'll admit, my own affinity for TG had always been almost entirely sonic in its orientation. As far as most of the content and subject matter was concerned -- all the invocations of Nazi atrocities, lustmord, psychopathy and whatnot -- from the very start it had always struck me as by far the least interesting thing about them.

But what of it? Genesis P-Orridge had said of the group's original formation: "'Let's not learn how to play music. Let's put in a lot of content... Let's refuse to look like or play like anything that's acceptable as a band and see what happens." In abhorrence to the popular music of the time, the members of TG devised their music as an attack upon the all of rock's shopworn conventions and formulae. Fair enough, but it echoes a not-uncommon idea that was being kicked around in the punk and post-punk years, an "anti-rock" sentiment given lip-service by the likes of John Lydon, Vic Godard, et al.

But as Simon Reynolds pointed out in his footnotes to Rip It Up and Start Again, TG were deeply "rockist" in certain crucial respects: "If you define rockism (as I do) an approach that privileges content, context, and intent, then Throbbing Gristle -- despite their contempt for rock-as-music -- were the ultimate rockists. Also totally rockist was their belief in authenticity, edge, rebellion, the outsider, épater le bourgeois/shock the square etc.". What's more, it could be argued that while TG's "shocking" and "confrontational" modus might be viewed as be polemically opposite that of a certain hedonistic/escapist tendency in late '70s rock, but it hardly places them outside the category; rather it's just the obverse of the same coin. That being the case, one could view the music of TG as being only slightly removed from the heavy and plodding "doom" or "downer rock" that Black Sabbath had pioneered earlier in the decade; complete with the motive of social critique -- if not moral protest -- lurking at the core of its content, albeit refracted through a different prism of strategic irony.

Punk had already seen to it that loud, distorted guitars were a primary staple of my musical diet during adolescence, But loud, distorted electronics -- that was another matter, and still very much a novelty/anomaly at the time.1 And of course, with TG and Cabaret Voltaire's abuse and misuse of cheap technology, the first-gen of industrial music earned itself a distinction of being the e-music equivalent of punk. What, after all, was the Cabaret Voltaire's "Nag Nag Nag" but a slightly retooled cover of "Pushin' Too Hard"?

Writing about a collection of Cabaret Voltiare's early home recordings some years ago, Reynolds offered that the early music of the Cabs and their first-wave industrial associates like Throbbing Gristle represented a non-nostalgic continuation of psychedelia's experiments in sonic manipulation, an aesthetic that that aimed "to blow minds through multimedia sensory overload" and adhered to a leave-no-sound-unaltered process that "adulterated rock's 'naturalistic' recording conventions with FX, tape splices, and dirty electronic noise." Listening to the contents of the first two discs of the set in question, the listener is inundated with dense washes of heavily-treated guitar, surges of shortwave radio noise, a pastiche of excepts from news and entertainment broadcasts, occasional chromatic smears of clarinet or soprano sax, and sporadic hints of a rhythmic pulse. While the Cabs were reputedly inspired to start making music in the first place by a mutual love for Roxy Music, from the sound of it their inspirational sources instead fell more squarely in the camp of Stockhausen, krautrock, musique concrete, and the BBC Radiophonic Workshop.

08 March 2012

This is Entertainment: Some Random Sidenotes

"'Tell me, pray,' said I, 'who is this Mr. Kurtz?'

"'The chief of the Inner Station,' he answered in a short tone, looking away. 'Much obliged,' I said, laughing. 'And you are the brickmaker of the Central Station. Every one knows that.' He was silent for a while. 'He is a prodigy,' he said at last. 'He is an emissary of pity and science and progress, and devil knows what else. We want,' he began to declaim suddenly, 'for the guidance of the cause intrusted to us by Europe, so to speak, higher intelligence, wide sympathies, a singleness of purpose.' 'Who says that?' I asked. 'Lots of them,' he replied. 'Some even write that; and so he comes here, a special being, as you ought to know.' 'Why ought I to know?' I interrupted, really surprised. He paid no attention. 'Yes. Today he is chief of the best station, next year he will be assistant-manager, two years more and... but I dare-say you know what he will be in two years' time. You are of the new gang — the gang of virtue. The same people who sent him specially also recommended you. Oh, don't say no. I've my own eyes to trust.' Light dawned upon me. My dear aunt's influential acquaintances were producing an unexpected effect upon that young man. I nearly burst into a laugh. 'Do you read the Company's confidential correspondence?' I asked. He hadn't a word to say. It was great fun. 'When Mr. Kurtz,' I continued, severely, 'is General Manager, you won't have the opportunity.'"

22 February 2012

This is Entertainment, Pt. I

(Or, A Few Casual Glances in the Rearview Mirror of Production)

Right, so sometime back I dashed off some remarks about the 'New Black', intrigued by what appeared to be a new and unexpected wrinkle the recent musicscape. Philip Sherburne and a few others had spotted a nascent subtrend on the horizon, some darkness starting to seep in around the edges. Whether of not it -- as a few asserted -- was a response by the younger set to the current conditions and their own diminished futures is arguable, if only because it seems like an over-reaching, overly-pat conclusion. At the very least, what I heard in some of the "new doom" stuff was a return to certain developments in electronic music from back in the mid-to-late nineties; developments which had –as with so much else about electronic music at that point – had either languished or been completely abandoned for the better part of the noughties.

Looking back, all I can do is shrug, because the trend has yet to lead to anyplace all that interesting. Lately, it seems there's been a glut of by-the-numbers "atmospheric" material bearing overwrought titles ("Burning Torches of Despair," anyone?) like those you usually find in the second-tier Black Metal canon.1 If that weren't tiresome enough, more recently it's pointing in the direction of a return of Power Electronics version three-point-oh.

At any rate, only reason I raise the matter again is in relation to a couple of Tihm Gabriele's recent columns over at Pop Matters. The most recent of which involves a discussion of the music of Throbbing Gristle in light of the latest round of reissues. In the opening paragraphs, Tihm gets to something I'd long wondered: What's likely to be your response to the music of TG if you've worked your to it through the reverse genealogy – after a long, latter-period steeping in the music of NIN, Ministry, Skinny Puppy and other such 2nd-gen industrial acts? Context is everything, of course, and while recounting his original back-when impressions, Tihm confirms what I'd always suspected -- that your reaction is (initially, at least) quite likely to be one of disappointment, if not confusion. That the music of TG -- so utterly bereft of many of the conventional rock/pop/dance structure and accessorizing niceties of later industrial acts -- is likely to strike such a listener as too rudimentary, too sonically crude and anemic.2

I'll admit that my original exposure -- back in the days that were closer to that in-situ context -- to the "first-wave" source of such stuff wasn't any resounding epiphany or a hugely rewarding experience, either. Scrounging around in the early eighties, I first came up with a copy of their soundtrack to Jarman's In The Shadow of the Sun. I was a little taken aback and intrigued by the alinear nature of the thing -- its buzzing and its occasional swells to abstract densities; with those noisy bits interlaced with long stretches of sparse, lulling near-inactivity; all of the above being filtered through some deliciously muddied subaquatic reverb. Intrigued, mind you, but hardly what I'd expected in light of what I'd read about them, had been poised to expect. (I was still a couple years shy of exposure to anything of the avant-jazz stripe like Art Ensemble's Paris Sessions, so it was new territory for me at the time.)

Greatest Hits soon followed and wound up making little sense to me at the time -- with its schizophrenic mixture of their more ironic pop-satire moments like "Hot on the Heels of Love" and "United" interlaced a smattering of noisier, more abrasive tunes (studio versions, mind you) from the less listener-friendly end of their catalog. A back-and-forth beween two opposite poles, perhaps; poles that (to my ears) fell on either side of The Normal's "Warm Leatherette," but still nothing that suggested anything aesthetically coherent, that pointed the way to larger gestalt. Maybe "Six Six Sixties" and "Blood on the Floor" suggested that TG warranted further investigation, or would I only wind up with more ironically faux-"sensual" Moroderesque disco thumpers? No idea -- too many mixed signals and I was lacking a copy of the codebook. Maybe, I suspected, it wasn't worth the bother.3

It wasn't until, shortly thereafter, I came across live recordings like Thee Psychick Sacrifice and Mission of Dead Souls that it all suddenly -- and very heavily -- fell into place. The loud, distorted electronics squealing through the hubbub; the frayed and viscerally thick bass tones; the improvisational approach to how any given "song" built (whether off of formless amusical meanderings or rifting around or off of some plodding or pummeling minimal rhythm) into a delirious density; all of it often interlaced with borderline unintelligible incantations and alingual howling.

In his recent A Cultural Dictionary of Punk: 1974-1982, author Nic Rombes makes a case for the American Midwest as a bedrock of early American punk -- specifically the "Rust Belt" network of steelworks and port cities that stretched fell along the East Coast and into the Midatlantic states before stretching far inland around the Great Lakes and into the central Plains. It is from these cities, he more or less argues, that the truest, noisiest, and most viscerally raw punk emerged; from the Motor City proto-punk of the Stooges, to the noise kicked up a few years later by the likes of Destroy All Monsters and Cleveland's The Electric Eels, the Pagans, and Rocket From The Tombs/Pere Ubu. In the entry "Cities, decay and beauty of," Rombes describes these parts of the American landscape through the lens of the mid-late 1970s:

"Cities of the American Midwest...approached postapocalyptic dimensions in your imagination. In downtown Toledo, the boarded up buildings offered a visual contradiction that verged on mystery: Here were beautiful building with ornate architectural details but whose windows were covered up with warped plywood. On one level you understood perfectly well what had happened: The perils of the economy were on the news every night. And yet, it still didn't make sense; you wanted to solve the contradiction of ruined beauty, either by restoring beauty or by pushing things further into ruin. Only later would it become clear that while disco had tried to push things back into decadent beauty, punk had tried to push them deeper into ruin. Whether you lived in these cities or not, you knew that what was happening there was a large-scale version of the same disaster that was playing out in small towns."

But a few pages later, the reader finds Rombes ventures in more nuanced territory. In the entry on "Class," Rombes draws a key distinction between American punk and the variety that hailed from the U.K.:

"There was a bit of Mad magazine in American punk from the mid-seventies, the kind of self-deprecating humor that comes from the confidence of empire. I should put my cards on the table now and say this: It comes down to nationalism. As bad as things were economically in the mid-seventies in New York...there was still a deeper assurance that the empire would not collapse."

Admittedly, the "industrial" moniker was a little problematic, or would become so as time wore on. I suspected as much early on. Industrial -- with its ironic echo of Futurism's celebration of technological prosthesis and the subsumption of nature into the modern culture of the machine age, as well as of Rusollo's "art of noises" in the form of mechanical rumblings and automated rhythms. But by some accounts, TG only adopted the term industrial as a cheeky referent to a preferred means of production and distribution of their work, and not as any sort of descriptive (let alone prescriptive) aesthetic.

But still, in a way it seemed appropriate enough at that particular moment in time, evoking as it did images of bleakness and "dehumanization" -- the blight brought about by the encroaching sprawl of manufacturing sector of certain cities, or the sociological decimation resulting when that same sector languished and dwindled in the transition to a post-Fordist economy. Whichever the case, the term was likely to paint a grim or foreboding picture in the listener's mind. But the matter of empire, of one's perception of the society in which one lives, brings something else into the picture -- something that falls between these two impressions, and perhaps connects them. Because whenever the word empire turns up, the concept of decline usually isn't far behind.

But like I said earlier, context (be it in-situ or deferred) plays a big part in the the matter of reception and interpretation -- be it in musical, cultural, or experiential terms. Where and how something fits (or doesn't) into one's frame of reference. About which, more in the next post.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

1. If there was one thing that certain proto-/first-wave "goth" acts understood that seems to have been lost on a majority of its later mutations, it's that sense of glam-era camp -- some degree of ironic distanciation from its adopted clichés.

2. For example, an enthusiasm for the "dub-house" output of the German Basic Channel/Chain Reaction imprint doesn't necessarily -- for some listeners, at least -- translate into an automatic appreciation or affinity for its "roots" (e.g., King Tubby et al.).

3. I believe Chris & Cosey's Trance found its way onto my turntable around this time; which didn't help clarify matters by any degree.

30 June 2011

Vinyl Reckonings

Some months back, Mark "K-Punk" Fisher curated a guest podcast over at Pontone. Beginning, ending, and threaded by the leitmotif of crackling vinyl surface noise and featuring tracks by the likes of Philip Jeck, William Basinski, and The Caretaker, the mix played out like a musical séance for moribund audio media. By way of accompanying liner notes, Fisher wrote about the spectral (there/not-there, presence versus absence) nature of phonography in relation to Derrida's ideas about the "metaphysics of presence," adding:

"With vinyl records, the more that you often hear is crackle, the sound of the material surface of the playback medium. When vinyl was ostensibly superseded by digital playback systems – which seem to be sonically ’invisible’ – many producers were drawn towards crackle, the material signature of that supposedly obsolete technology. Crackle disrupts presence in multiple ways: first by reminding us of the material processes of recording and playback, second by connoting a broken sense of time, and third by veiling the official ‘signal’ of the record in noise. For crackle is of course a noise in its right, a ground becomes a figure."

The concept of spectrality and haunting was a central theme in The Caretaker's project from the very start, with the artist having derived both his moniker and his creative premise from Kubrick's The Shining. Basinski emerged on the scene some years ago with his acclaimed requiem cycle The Disintegration Loops, which deals with mortality and entropy by way of the material and sonic degradation of timeworn magnetic tape. And Jeck's work owes it melancholy creakiness to the notions of obsolescence and abandonment it invokes...

Many of these tropes harken back to the work of noisician and artist Christian Marclay, who himself began working with LPs and record players back in the late 1970s. From the beginning, Marclay was fascinated the materiality of recorded media, especially with the record LP as a physical object – as document of a performance, an ephemeral and intangible moment in time, arrested and affixed in material form, commodified and mass manufactured in serial units, circulating in the cultural domain of commercial society.

Plasticity aside, there was also Marclay's affinity for "the unwanted sound." Primarily this was the sound of technology being intentionally misused and abused, but it was also the sound – or the combination of sounds – of all the bygone and discarded musical products of previous years and decades, now amounting to only so much landfill fodder or cents-on-the-dollar clutter in the bins of second-hand music shops. All of it – the exemplars of former zeitgeists, even – rendered equal by its outmodedness, its use-value amounting to little more than the part it plays in a layered cacophony. Same too with Marclay's later works involving album sleeves or other formats such as audio tape – in the end it comes down to the utility or stylishness of last year's model seeming so remotely quaint or clunkily alien when seen from just a little further down the evolutionary chain.

Sure, LPs and turntables were the dominant technology for home listening at the time that Marclay first started working with them. And he wasn't the only one messing about with gathering and manipulating these items for the sake of making noise in the late 1970s.

Some quotes...

GRANDMASTER FLASH: At the time, the radio was playing songs like Donna Summer, the Tramps, the Bee Gees – disco stuff, you know? I call it kind of sterile music. Herc was playing this particular type of music that I found to be pretty warm; it has soul to it. You wouldn't hear these songs on the radio. You wouldn't hear, like, 'Give It Up or Turn It Loose' by James Brown on the radio. You wouldn't hear 'Rock Steady' by Aretha Franklin. You wouldn't hear these songs, and these are the songs that he would play.

TONY TONE: I was working in the record shop, so I used to know all the records....but I didn't know the records Herc was playing. So now it's grabbing me, now I'm trying harder to order them for my record shop, but I can't find them 'cause they're not records that are selling right now – they're older records, jazz records, whatever.

So "digging" always involved hunting and unending quests to excavate the rare and the funky, but it also – once upon a time – meant sifting through the unwanted and the forgotten. Used bins, "cut-out" bins, thrift stores, or even – in the case of Grandmaster Flash – running the risk of catching an ass-whooping from your pops after being told, "Don't ever touch my records."

By now it's a little trite to make a case for framing the creation of cutting and scratching (and eventually sampling) as a street-level, mother-of-invention version of musique concrète. But one may as well make one for the first-gen practitioners of hip-hop DJing – Herc, Bam, Flash, and many others – as being early pioneers of some musical equivalent of salvagecore, if only for the sake of "keeping the funk alive" in the face of the monocultural sweep of disco.

But: Surface noise as sonic patina – as signifier of the music's physical format and vintage, as a deliberately skewed figure/ground relationship. That's a later and different development. Initially, it was something to be avoided at all costs – only so much noise contaminating the signal, or undesirable syntagmatic slippage.

If the nature of the "hauntology" rubric has been difficult to nail down with any sense of certainty, it might be due to the facts that (a) it was never that firmly formulated of a concept to begin with, and (b) the term and corresponding concept suffered a denotational shift as soon as it began to circulate more broadly. At first it referred to something slightly intangible and impressionistic; something not too different, in certain ways, from Freud's notion of the Uncanny (especially in that both involves varieties of cognitive dissonance and a sense of dislocation or "dyschronia"), and how it plays out aesthetically.1 But soon enough discussion of the hauntological began to focus less on the nature of the sensation or condition, and rather on the mere things that might bring the notion to mind. And by things I mean just that – books, toys, films and TV programs, photographs, and various other ephemera from one's childhood, from prior eras. In the end – objects and the associations projected onto them. Which, in many ways, borders on mere, mundane nostalgia of a sort. Not that nostalgia doesn't factor into this in the first place, but that's a whole other line of theoretical speculative – a line that could draw from a rich backlog of philosophic ink that's been spilled on the topic over the past century and a half.

And I'm fairly certain that aspects of all of this overlap – however tangentially – with the topic that Simon addresses in his new book Retromania: Pop Culture's Addiction to Its own Past. I haven't read or even gotten a copy yet, so I can't say for sure. But Alex Niven recently posted some thoughts on the book's focus that struck an intriguing note...

"Moving quickly into the realms of massive theologico-cultural conjecture, the whole retromanic thing seems to me to have something to with the occlusion of death in a modern technocratic society. Death has replaced sex as the great taboo. We just don't know what to do with death – the one thing a culture of pluralism and excess cannot find a space for: the absoluteness of an ending. Hence, things that are obsolete become weirdly fetishized. The sobering fact that the past is absolutely no more is replaced with a sort of adolescent inability to let go of childhood toys and move on."

An "occlusion of death" perhaps, a way of stacking some barricades against the door in an effort to hold off a particular type of existential dread. Or what happens when a schizophrenic economy of scarcity and surplus flatlines into one of equally-available "pluralism and excess," and – sensing it may have hit some teleological impasse – suffers an extended spasm of insecurity in regards to where it was all supposed to lead in the first place, and compulsively doubles back on itself in a frenzy of archiving, retrofitting, taking inventory and what-have-you.

Static, surface noise and signal interference, however, is more bluntly about the big D. It ultimately points to the corporeal fragility and impermanence of it all, a nagging momento mori that nothing will ever ever be as it was despite whatever effort or technology is employed to stave death and degeneration away. If, as K-Punk once phrased it, the history of recording constitutes a "science of ghosts," then the metaphysics of crackle (or of the sputtering, atomizing digital glitch) serves as a reminder that it's an imperfect science. Or as he stated early in the discussion, the figure and ground are inextricably linked by the sheer materiality of the medium...

The spectres are textural. The surface noise of the sample unsettles the illusion of presence in at least two ways: first, temporally, by alerting us to the fact that what we are listening to is a phonographic revenant, and second, ontologically, by introducing the technical frame, the unheard material pre-condition of the recording, on the level of content. We're now so accustomed to this violation of ontological hierarchy that it goes unnoticed.

The rest, as they say, is just noise.

1. Or I suppose another way that this could be discussed, given the excretal economy of consumption and waste that all of this points involves, might be by way of Kristeva's notion of the Abject.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

WHAT

Headspillage, tangents, fragments & ruminative riffing. Guaranteed to sustain a low level of interest, intelligibility, or lucidity for most outside parties.

CONTACT:

greyhoos[at]gmail[dot]com

Elsewhere

(Contributing)

Esoterica

Effluvia

Edificial

- a456 ■

- Archiplanet Wiki ■

- Architectural Theory ■

- Brutalist Revival ■

- Critical Grounds ■

- deconcrete ■

- Diffusive Architectures ■

- Down with Utopia ■

- dpr-barcelona ■

- Fantastic Journal ■

- Iqbal Aalam ■

- Kosmograd ■

- Kostis Velonis ■

- Lebbeus Woods ■

- Life Without Buildings ■

- mammoth ■

- Measures Taken ■

- RNDRD ■

- Sit Down Man, You're a Bloody Tragedy ■

- SLAB ■

- Strange Harvest ■

- Subtopia ■

- The Charnel-House ■

- The Funambulist ■

- This City Called Earth ■

- Unhappy Hipsters ■

Etcetera

Ekphrasis

- 555 Enterprises ■

- A Scarlet Tracery ■

- Blissblog ■

- Dave Tompkins ■

- David Toop ■

- Devil, Can You Hear Me? ■

- Go Forth and Thrash ■

- History Is Made At Night ■

- Irk The Purists ■

- Nic Rombes ■

- nuits sans nuit ■

- Pere Lebrun ■

- Phil K ■

- Philip Sherburne ■

- Retromania ■

- The Fantastic Hope ■

- The Impostume ■

- Vague Terrain ■

Epistēmē

Eurythmia

- 20JFG ■

- Airport Through the Trees ■

- Blackest Ever Black ■

- Burning Ambulance ■

- Continuo ■

- Continuo's Docs ■

- Cows Are Just Food ■

- Cyclic Defrost ■

- Foxy Digitalis ■

- I Am the Real Kid Shirt ■

- Idiot's Guide to Dreaming ■

- Johnny Mugwump ■

- Kill Your Pet Puppy ■

- Lunar Atrium ■

- MNML SSGS ■

- Modifier ■

- Pontone ■

- Resident Advisor ■

- RockCritics.com

- Root Strata ■

- Sonic Truth ■

- The Liminal ■

- The Quietus ■

- Tiny Mix Tapes ■

- Waitakere Walks ■

- WFMU Beware of the Blog ■

Ectoplasm

Ephemera

- 50 Watts ■

- Architecture of Doom ■

- Bibliodyssey ■

- Breakfast in the Ruins ■

- But Does It Float ■

- Casual Research ■

- Cinebeats ■

- Critical Terrain ■

- D. Variations ■

- Daily Meh ■

- Dataisnature ■

- every other day ■

- Ffffound ■

- Hate the Future ■

- History of Our World ■

- Journey Round My Skull ■

- Landskipper ■

- lI — Il ■

- Lumpen Orientalism ■

- mrs. deane ■

- Nightmare Trails at Knifepoint ■

- no blah blah ■

- No Future Architects ■

- Open University ■

- Paleo-future ■

- Pietmondrian ■

- random index ■

- Smiling Faces Sometimes ■

- Today and Tomorrow ■

- twelve minute drum solo ■

- Utopia-Dystopia ■

- We Find Wildness ■

- XIII ■

- |-||-||| ■

Powered by Blogger.