Linkbar

Showing posts with label music. Show all posts

Showing posts with label music. Show all posts

07 September 2017

Because

Honestly, back in the days when Julian Cope's Krautrocksampler doc became the Young Person's Guide to Same, I took issue with the author's assertion that German prog was part of a concerted effort to shed all all Anglo-American influences. True enough if you're listening to Neu!, Harmonia, Kraftwerk, Cluster, and Faust; but not much of the case at all when applied to most of their German prog contemporaries.

And not so true much early Can, either; which -- despite however adventurous it aiming to be -- still adhered to the arc set by Anglo-American psych/blues/"freak-out" models. But that would change soon enough , all such stuff was gradually stripped away and the music pared back to its base elements. Which is probably why Ege Bamyasi and Future Days remain the albums I most often revisit. With the former album, the band starts to shed the aforementioned baggage -- with Czukay's bass and Jaki Liebezeit's drums brought prominently into the foreground, guiding much of what transpires, mixed and crafted in a way that created an uncanny sense of sonic spatiality. The latter album followed further down that path -- far enough to achieve its own peculiar musical universe.

It was heartening to see Czukay paid proper tribute when the post-rave electronic music boom of the late 1990s came along -- his contributions as an e-musik pioneer widely recognized, thus giving him a second life with a new generation of listeners. I recall clips of him playing as festivals, bobbing and dancing around behind racks of new-gen gear, delighted that the world still kept offering him the means to further explore musical ideas that had gotten into his head from his early days as a Stockhausen student.

07 October 2016

Art Decade (Redux))

Yes, so that last bit was re-post of something written five years ago, originally hammered out for the "the 1970s blog" team-effort thing. At the time, I didn't originally set out to write about David Bowie, per se. Rather, I'd been thinking about the American popcult fascination with many things German, particularly Weimar-era Berlin -- a common fetishizing of its decadence, of its status of a place teetering on the edge of an historical abyss that it would soon topple into. And then, reading something about Bowie's time in Berlin and the events that led him there, I decided to use the Bowie angle as a thread on which the loosely hang a number of other themes and thoughts.

And I was prompted to go ahead and re-post the piece this back while I was reading Paul Morley recent volume, The Age of Bowie. When it comes to Bowie's Thin White Duke year and what followed, Morley takes no discernible interest in Bowie's drug habit and near crack-up, focusing instead other aspect of the the artist's work and career. But he does mention, more or less in passing, something else that seldom comes in most accounts -- something far more pragmatic and less romantic that might help cut through the fog of mystique that long ago coalesced around Bowie's "Berlin trilogy" of albums.

That being the artist's business deal with manager Tony Defries and Mainman, Ltd.. In 1975, Bowie apparently realized that the arrangement was stacked too heavily in Defries's favor and fires him. But he still has some years left to go before his contracts with Defries and RCA expire. So he spends the next several years doing what wants, working with whom he wants, recording where he wants -- releasing darker, more esoteric and "experimental" albums that RCA is increasingly vexed to wring any singles out of; and when they do manage to do so, the tunes don't chart as highly or as frequently as earlier work (thus perhaps insuring that Defries's royalties from newer work dwindles).

So, with those three albums -- as well as a second live album, two "best of" collections, plus a children's record by way of an adaptation of Peter and the Wolf on which Bowie provides the narration -- he finally fulfilled his contractual obligations for RCA when he handed over 1980's Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps).

But his contract with Defries didn't run out until 1982. Something that Bowie had clearly been anticipating and planning around, when you consider the way he steered his career in a more commercial direction with the album he released the following year.

Labels:

misc.,

music,

notes

0

comments

04 October 2016

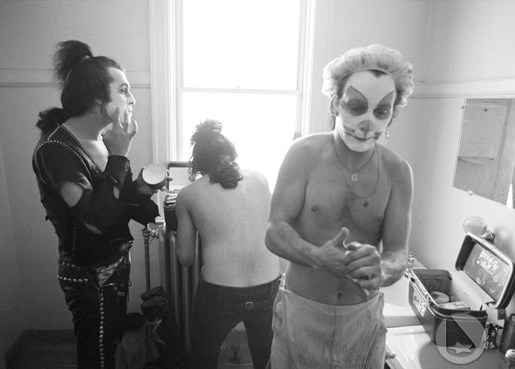

Look Good in Ruins

(or: Twenty-five Tangents about Bowie in "Berlin")

Archival post, originally posted at ...And What Will Be Left

of Them?, April, 2011. It's a shame I can't re-post all of the

amusing responses that piled up in the comments section

1.

By all accounts, he had to get away from L.A. That much is a matter of undisputed public record. Some claim it was little more than a tax dodge, but others argue it was Bowie's attempt at breaking the maeslstrom of drugs and increasing psychosis that was consuming his life -- the obsession with Aleister Crowley, the traffic, escalating paranoia, the $500-per-diem cocaine habit supplemented by a diet of milk and peppers. Or maybe it was all of the above. But it had to start with leaving, getting out and getting away, extricating oneself from certain endangering circles, breaking with destructive habits and everything that fuels or enables them, and hopefully changing course and salvaging what's left of one's creative energies before it's too late. First to Switzerland, then -- eventually -- to Berlin. Leaving Los Angeles and all of its snares and poisonous associations behind. To hell with it all. Looking back, he would later say of Los Angeles, "The fucking place should be wiped off the face of the planet."

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.

No big surprise, really, that Bowie would inevitably wind up in Berlin. He'd been enthralled with Germany for some time -- fascinated, as some recent recorded comments and reputed gestures suggested, to a worrisome or problematic degree. He was deeply taken with its art and its music, with the decadent cabaret culture of the Weimar era, and -- more alarmingly -- with a certain sordid chapter of its 20th-century history.

But mainly it seemed like a good place to go to detox and collect one's wits. Bleak, depressed, somewhat coldly (and dingily) modern, furtively wrestling with its own history in the most repressed of ways, physically divided, socially and politically adrift in the throes of its Cold War limbo. That was the impression of the place as it existed at the time, anyway – the picture that the word "Berlin" commonly painted in a person's mind. A "come-down" city if ever there was one. You wander down a given city street, only to come to its sudden and abrupt end, the point of stoppage at which you find yourself facing the Wall. Some histories aren't so easily left behind, some histories leave harsh reminders.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.

It was Christopher Isherwood who put the idea of moving to Berlin into Bowie's head. Bowie had long been a fan of Isherwood, whose Goodbye to Berlin had undergone a recent revival in popularity from loosely providing the inspiration for the musical Cabaret. Attending the Los Angeles stop of the Station to Station tour in 1976, Isherwood and artist David Hockney had made their way backstage to converse with the singer afterward. The topic of Berlin came up. Isherwood would later claim that he tried to disabuse Bowie of the notion of going there, going so far as to dismiss the city as "boring." No matter, as it prompted Bowie to decide that a lack of distractions and some anonymity were what he needed to clear his head, and it wasn't much later that he started packing his bags.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.

Bowie wasn't the only one fascinated by Berlin in the 1970s. Far from it. A quick survey of the American cultural landscape revealed that a certain number of people in the U.S. shared a similar interest. Lou Reed's Berlin LP might've played some small part in the matter, with the way it sketched its setting in the gloomiest and starkest of tones. And there was also the popularity of the Broadway and film productions of Cabaret. Plus, the novels of Heinrich Böll and Günter Grass sold modestly well, with the films of Herzog and Wertmüller and Fassbinder and Wenders drawing crowds at the cinema in New York and reviews from urbane film critics.

As far as how the idea of Berlin was conceived and held in the American public imagination -- it represented something, must've served as some kind of metaphor. But a metaphor for what? Nobody ever said precisely, and perhaps nobody actually knew. Something having to do with trauma and unthinkable sins, with atonement and the weight of history, about rebuilding from the wreckage without looking back, of not being able to speak of the past, of living in a historical limbo. And about modernity. Because Berlin seemed deeply modern, but in a way that was as hard-won and enburdened as any form of modernity could be.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5.

"Amerika kennt keine Ruinen," art historian Horst Janson reputedly wrote in 1935. America knows no ruins. Ruins, as such, serve as a marker of history; of the past, of civilization having peaked and waned. In its sui generis exclusivity, America in the 20th century say itself as the embodiment of modernity. History was for the Old World, something that effected various elsewheres -- deeply European in its fatalism and determinism. To acknowledge it, to speak its name, meant playing the defeatist's card -- an admission of falling victim to causal forces beyond one's control. Never, never, never. America isn't shaped by history, America makes history. America knows no ruins because it is continually razing the grounds and building anew.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.

Unlike the projects that preceded it, Bowie's Young Americans blue-eyed soul schtick seemed like an aesthetic dead-end from the start -- conceptually limited, not the sort of thing one could build on, could take in any further direction. Transitioning into his European, world-wearied proto-New Romantic persona as the Thin White Duke the following year, Bowie would revisit the formula on Station to Station, albeit in a revamped, more dense and shadowy form.

Case in point, Station to Station's "Stay." Abetted by the chops of a couple of former members of Roy Ayers Ubiquity, the song showcases Carlos Alomar and Dennis Davis tucking deeply into the groove, getting louder and more open than they did on most of Ayers's recorded outings. "Stay," Bowie croons, although it sounds more like a suggestion than a plea. He sounds numb or placidly transfixed to the spot, while the band piles in a car, stomps the accelerator pedal, and screeches off toward their own destination, all but leaving the frontman in the dust. Stay? The singer was already in the act of grabbing his coat and heading toward the exit.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

|

Left: Victoria Station, 1976. Right: Martin Kippenberger, Ich kann beim Besten Willen

kein Hakenkreuz entdecken ("I Can't for the Life of Me See a Swastika in This"), 1984.

|

7.

At Victoria Station in London, the camera shutter snaps and catches Bowie waving to fans, his arm in mid-sweep. The photo then runs in a number of tabloids, each claiming that the singer was seen giving the Nazi salute. Of course, that's just the tabloids being the tabloids. But it certainly didn't help that at about the same time he would make a remark in an interview about how Britain could really "benefit from a fascist leader." It was at that point that people started to wonder about the depth and the nature of the singer's Teutophilia, or if all that cocaine hadn't irreparably fucked his brain.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8.

In 1969, the artist Anselm Kiefer made a series of excursions across Europe. It was the earliest stage of his career, and the journey was the basis for a project -- a photographic travelogue titled Occupations. In each of the resulting photos, we see Kiefer at each of his stops giving the fascist salute.

There's something deeply, ironically comical about the series, as we see the artist as a lonely pathetic figure isolated within the frame, standing at attention with his arm held stiffly in the air. In Rome, at Arles and Montpellier, facing the ocean à la Friedrich's Wanderer Above the Misty Sea. An isolated and abject figure, a bathetic caricature of nationalist sentiment and imperial hubris -- ciphering away in empty and indifferent spaces, dwarfed by the surrounding landscape and architecture, repeating a delusional and ineffectual gesture ad absurdum, summoning the spectre of a lapsed and doomed history again and again and again. As if to drive the issue home with a visual pun, in one shot we see Kiefer in the same pose while standing in silhouette against the window in a trash-strewn apartment. Lebensraum. Of course.

All irony aside, the series still managed to piss off a lot of people at the time.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

9.

Albert Speer knew the value of history, and he also knew the importnace of ruins. During the 1930s, Speer was developing and promoting his own Ruinenwerttheorie ("Theory of Ruin Value") as the overarching principle for the imperial architecture of the Third Reich. The power of the state was to be exemplified in its architecture, he argued; architecture which would stand and sprawl boldly and proudly, endure for a millennium, and then look good in ruins as "relics of a great age." As the Reich's chief architect, Speer was most notably responsible for designing the Nuremberg Zeppelin Field and the German Pavilion for the 1937 World Exposition in Paris. But by dint of their grandiose and unrealistically ambitious character, most of Speer's projects never made it beyond the drawing-room stages. Among his grand, unrealized visions was that of overhauling the capital city of Berlin in a monumentally neoclassical fashion, in the process rechristening the new megalopolis Germania.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

10.

Reputedly, Bowie's interest in Berlin was mainly artistic in origin. As an aspiring painter, he'd always admired the German Expressionists. And in the middle of the 1970s, in the blur of cocaine and fame and things going off the rails, he was gravitating again to that initial interest in putting paint to canvas; devoting more time to doing so, if only as a means of (re)focusing his creative energies. Some stories have it that before he left for Berlin, he'd been discussing the possibility of doing a film called Wally -- a film based on the life of the Viennese proto-Expressionist artist Egon Schiele.

Nothing ever came of that project, so eventually he had to settle for being in Just a Gigolo instead. But looking at the cover of "Heroes", you might think Bowie was having a flashback to his early days as a street mime. If not that, then maybe he was running through a series of contrived and contorted poses reminiscent of Schiele's numerous self-portraits.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

11.

Common side effects of advanced cocaine use: Possible neurological and cerebrovascular effects, including but not limited to, subarachnoid haemorrhage, strokes of varying aetiologies, seizures, headache and sudden death. Symptoms might also include chest pains, hypertension, and psychiatric disturbances such as increased agitation, anxiety, depression, decreased dopaminergic signalling, psychosis, paranoia, acute and excessive cognitive distortions, erratic driving, writer's block.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

12.

A severe and minimal stage setting, Kraftwerk piped in over the p.a. before the performance, followed by Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel's surrealist short film Un Chien Andalous being screened above the stage. Bowie would claim that the idea for the stark black-and-white stage design was inspired by German Expressionist cinema, especially Metropolis and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. All of it signifying the "shock of the new" -- the adversarial tradition of modernism and the avant-garde in twentieth century art, complete with its aesthetic credo of relentless progress and innovation, of perpetual revolutions in artistic form and content.

The Third Reich, however, had no truck with the avant-garde. Goebbels (the failed novelist) had tried to argue with der Führer (the failed painter) about the nature of the regime's cultural policies, making the case that the ideas of a dynamic and forward-thinking society should be embodied in art and literature that was boldly and unapologetically modern. But Goebbels lost that argument, and was given the order to abolish all traces of the avant-garde -- to rid the culture of all art that Hitler deemed "degenerate" and "foreign" and poisonous to the constitution of a "pure" German culture. With that decree, all enclaves of modernist art, literature, and film in Germany were abruptly and sweepingly shut down, wiped out, or driven into exile.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Labels:

1970s,

art history,

cultural history,

film,

music

0

comments

16 August 2016

Because

RIP, Bobby Hutcherson

{ Post-posting afternote: Yeah, I know, I exclusively drew from Hutcherson's early career. Shrug. There are a number (low number) of other notable vibraphonists throughout the history of jazz. But as far as depth, range, and flexibility, Hutcherson may've been the one who best demonstrated it's full potential as a non-novelty/surplus component of a jazz ensemble. Especially the way he used the instrument to bridge the melodic/percussive vs strictly-percussive properties of the piano and drums...best exhibited when he was working between an eccentric pianist/composer like Andrew Hill, and a drummer/composer (yes, that's "a thing," although very rarely) like Joe Chambers. Wonderfully guiding things in the right stretches and spaces; at others times -- espec as a sideman -- adding accentuations and highlights, or (as on the Henderson and Patton pieces above) helping drive the whole joint into rhythmic overdrive. }

Labels:

music,

RIPs

0

comments

10 March 2016

Frequency Range, II

The second, and last, part of my 20-plus years of locale-specific bass musics travelogue. Last time I dealt with my years living in the American south. This time we head to parts north...

Chicago, 1993-4: What's That Sound?

At the time, I had no idea of what it was I was kept hearing -- something I occasionally hear booming from jeeps as they passed through the block. Hilariously uptempo, threaded on very tight loops of sped-up, stuttering vocal phrases, extremely minimal with only incremental shifts and modulations. At one point, I happened across it on local public access TV, some talent-show program with a bunch of southside high-school kids dancing to it -- slow, rolling bodily undulations passing from head to toe and back again, from limb to limb. I didn’t hear the music all that frequently, when I did it was only from a distance, and it seemed to have come and gone within a season of two. In retrospect, I thought maybe I was hearing an example of Baltimore's "dew doo" beat making an inland incursion, but years later (see last entry below) would realize that what I'd been hearing were local "ghetto house" tracks.*

Chicago, 1993-4, Pt. II: Jungle and Drum'n'Bass

U.K. import tangent, number two. Simon's already weighed in on jungle in a pair of posts, so I’ll gladly defer to authority on the matter.

The first time I heard jungle, via a mixtape I'd picked up, I had no idea what I was hearing -- was startled and bemused by the rush and clatter of the accelerated BPMs.** By the third spin, the music had not only clicked with me, but I had decided it was among the most immersively gorgeous music I’d ever come across. The undertow of the bass was what pulled me in, the way it moved at a fraction of the pace of the drums, provoking the sensation of being pulled into a temporal flux.

06 March 2016

Frequency Range, Interlude

At which point Simon delves into early hip-hop. Truth be told, I was planning on passing on that one. But since I spent most of the music’s “mid-school” years totally immerse in the stuff, I naturally have a few things to contribute on the topic...

(Caveat: Since you're listening to this on a computer, a decent set of headphones are recommended.)

What, no mention of Run DMC? The Tougher Than Leather album sported a number of tunes where the Run DMC took a turn away from the stark minimalism of much of their prior material, going with a sound that much fuller and more spacious. I recall a critic at the time saying these two tracks in particular sounded had taken up residency in outer orbit, rapping and mixing while springing off the the space-station walls in zero gravity. An image that has stuck with me over the years (particular when the reverb on the punctuating snare shot darts through the mix of "Run's House). Jam Master Jay was the man, but apparently the bass on the above can be partly attributed to co-producer Davy D..

Simon cites the Beasties. From License to Ill, I remember "Paul Revere" being the cut that dudes used to use to give their woofers a workout. Personally, I had a love/hate relationship with the Beastie Boys in those years, which had taken a dissenting tilt toward the latter by the time Paul's Boutique came out. A friend loaned me his copy, I gave it few spins, and my feeling was that if someone could somehow release an all-instrumental version of the thing, I'd probably be all over it. Thankfully, the production duo that was the Dust Brothers partially obliged me via a couple of 12-inch remixes. The bass bits on their overhaul of "Shake Your Rump" were particularly satisfying.

And as far as live-group era Beasties are concerned: "Jimmie James" was a tune that rode its smoked-out bass line mighty nicely.

A favorite block-rocker from what could be considered the golden era’s swansong summer that was the summer of '93, when the version that appeared on the b-side of the Masta Ace Inc.'s "Slaughtahouse" 12" became the definitive jeep beats of the season. An ode to the "quad"-pumping lifestyle and incivic disturbance coming from the most unlikely of locales -- the (previously) bass-anemic upper East Coast. Sure, the bass on the thing was dope, but I‘ve always found it deeply funny at the same time -- maybe because it sounds kinda "sick" in both senses of the word.

Speaking of jeep beats...

03 March 2016

Frequency Range, I

And the conclusion of my contributions to the extramural Blissblog bass poll/topic, intro...

This brief article, which turned up in an early post from Simon's polling, touches on some transmusical fundamentals. Because -- yes -- as the title of an old Smith & Mighty albums once had it, “Bass is Maternal.” Which may all seem a bit intuitive, a bit too physio-/psychoacoustics 101. Because pulse component aside, those low frequencies (espec when majorly boosted via car stereos or massive club PAs) are also deeply corporeal. They envelope and penetrate; making viscera quake, thick stone walls shake, and I don’t doubt it that it's also the ammo for recent sonic weaponry tech.

All of which also partly explains why -- yes -- there are such a things as deaf raves.

I was a little predisposed to bottom-heavy music. My hearing was always a little “hyper-acute” with high-frequencies. Maybe this had something to do with why I avoided whole genres of music that were too tilted to activity in the high-end registers, and more prone responding to tilted toward the opposite end of the spectrum.* Over the years I’ve found myself exposed to a number of varieties of “bass music” -- the sorts that could be considered as constituting some kind of (to borrow one of Simon’s terms) a ‘nuum. But aside from being bass-heavy, the peculiar thing about them is that they each seemed to be specific to certain places/cities/regions. If not being the product of some homegrown locals-only restlessness.

The following is more or less a "doof-doof" travelogue, playing out over the course of 25 years of happening to be in certain places at certain times...

I: 1980s: SOUTHERN/MIAMI BASS

Being a teen in the Deep South of the U.S. after hiphop broke was a dicey affair, especially if you were wanting to hear more and more of it. Throughout the first half of the 1980s, most hiphop from the upper east coast didn’t filter down south. I guess much of it proved too “urban” in its perspective to appeal to places that were at best only semi-urban. But electro-funk took in a big way early in the ‘80s, and had a lasting influence in the southeast. Kraftwerk’s “Numbers” and “Tour de France” got a lot airplay on the non-white radio stations. Stuff like Twilight 22’s “Electric Kingdom” and Egyptian Lover went over massively in clubs and on boom boxes. Some of it brought “that boom” that was popular with a certain demographic. But not enough of it. As Dave Tomkins wrote in his “Primer to Miami Bass” piece in The Wire many years ago, the sub-Mason-Dixon response to much of what was coming from up North was that it involved too many guys in spacesuits and not enough boom.

So the locals started making it for themselves, tweaking the music to their own tastes. And sure, originally the southern booty-bass sound did hail from Miami and parts thereabouts at first; but within a few years it was also coming out of Atlanta and Houston and elsewhere in the SE region. I can remember numerous nights of driving around on a Friday or Saturday night, punching across the radio dial until I found a program where a DJ was playing a weekend party set. Track after track of punchy bass that had my ass careening in the driver’s seat while I steered down thinly-travelled roads in the darkness. At some point me figuring I was listening to the 181st (then 182nd, & etc.) remake of “Planet Rock”, which I was just fine with.**

It was so prevalent, that one could be excused for thinking that that was what most of the hip-hop universe consisted of. So many years later I was a bit thrown when James Lavelle put together a compilation of early tracks by DJ Magic Mike, and I read reviewers writing things to the effect of: “Arrrrgh!! Why am I only now hearing this stuff?” Considering that it was so inescapable to me once-upon-a, I couldn't help being befuddled by finding out that the music was such a marginal & provincial thing.

EARLY '90s, PT. 1 - BLEEP & BASS:

Still a victim of geography at this point. A lot of early U.K. House/early Rave music didn’t make it my part of the country. College kids were I was at the time were in the thrall of lots of northern European “industrial dance”drek. What little early rave fare trickled my way seemed alright enough, because I welcomed the energy. Functional for the dance floor, but didn’t strike me as the sort of stuff I’d want to much time with outside of a club setting. Until a number of tracks popped up that really caught my attention, seemed to be going in a direction that really appealed to me. More bass, and a distinctive use thereof. And, just generally, electronic music starting to move in the direction of kicking its made-upcsounds every which way around inside the listeners head. Years later I would learn that all of these records had something in common; that being that they hailed from city of Sheffield and its surrounding area, and could be filed under the category of the “Bleeps and Bass” subgenre.

EARLY '90s, PT. 2 - HIT THE BREAKS

Around the same time, I was moslty immersing myself in what's not looked backed on as "midskool" hiphop. I also stumbled across a few tunes that excited me tremendously, because they signaled the entry of breakbeats into the rave-culture mix. But at the tim had no idea about “‘ardkore” being a thing, let alone a very divisive, scene-splitting thing across the water. Only that it sounded like something I’d been eagerly waiting for.

But we need to talk about a couple of Atlanta joints. First off...

True, Rob Base & E-Z Rock had had a big big hit using the Lyn Collins "Think" break on their mega-hit "It Takes Two" in 1988; and over the next several years a number of tunes by high-profile acts milked further hits with the same break. But this Atlanta act pitch-shifted it into higher, more punchier bpm territory in a way that must've given a lot of people ideas. The title of the track is sampled from a 2 Live Crew number, and shortly thereafter Luther Campbell & crew in down in Miami responded to 2 Hyped Bros's jawn by doing their own version of the above, speeding it up even more and adding heaps of club-flattening bass.

And then there's this...

B-side wins again, by way of Mantronix-style editing being flipped into full warpspeed. This time via a reissue of Atlanta's Success-N-Effect debut track "Roll It Up N___a", this time with a instrumental remix that had been outsourced to Miami DJs Charlie Solana and Felix Sama, who gave in a Mantronix-in-warpdrive overhaul, using a chopped-up sample of the Winstons' "Amen" break for the benefit of maximum punchiness. If Frankie's Bones's account is to be taken as vaguely factual, then he heard it at the time and started playing it in NYC, and from the audience reaction decided it was worth flipping to Carl Cox, who then took it to overseas connections, where it helped inspire the beginnings of UK breakbeat 'ardkore. Perhaps partly true, or maybe total bullshit, but most likely doesn't matter (except for those that might be looking to get all chauvanistically "nativist" about such stuff).

And admittedly, here's where things get tricky. Because it's the point at which the the symbiosis of bass and kick drum comes in, which could argue consists slippage or cheating on my part. But since the 808 was what got this particular nuum rolling, it totally counts by my (and plenty others') reckoning.

Whatever the case, both the "dew doo" [sic] and "amen" breaks will factor heavily in second (more Northern) part of this thing. But for now, that's the end of Part I.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

* This is not bullshit. My wife thought it was, until she became an audiologist and put me into a testing booth. Not to gloat or brag, but -- even after years of my abusing my eardrums night after night spent blasting music through headphones, or a fair number of nights spent in clubs with the shittiest acoustics -- in the end my claims were fully vindicated by the test results.

** NOT ENTIRELY TRUE. Lyrics were another matter. Here there are some problems. Not the least of which was the annoying habit of the vocals consistently being placed far too high/frontally in the mix.

This brief article, which turned up in an early post from Simon's polling, touches on some transmusical fundamentals. Because -- yes -- as the title of an old Smith & Mighty albums once had it, “Bass is Maternal.” Which may all seem a bit intuitive, a bit too physio-/psychoacoustics 101. Because pulse component aside, those low frequencies (espec when majorly boosted via car stereos or massive club PAs) are also deeply corporeal. They envelope and penetrate; making viscera quake, thick stone walls shake, and I don’t doubt it that it's also the ammo for recent sonic weaponry tech.

All of which also partly explains why -- yes -- there are such a things as deaf raves.

I was a little predisposed to bottom-heavy music. My hearing was always a little “hyper-acute” with high-frequencies. Maybe this had something to do with why I avoided whole genres of music that were too tilted to activity in the high-end registers, and more prone responding to tilted toward the opposite end of the spectrum.* Over the years I’ve found myself exposed to a number of varieties of “bass music” -- the sorts that could be considered as constituting some kind of (to borrow one of Simon’s terms) a ‘nuum. But aside from being bass-heavy, the peculiar thing about them is that they each seemed to be specific to certain places/cities/regions. If not being the product of some homegrown locals-only restlessness.

The following is more or less a "doof-doof" travelogue, playing out over the course of 25 years of happening to be in certain places at certain times...

I: 1980s: SOUTHERN/MIAMI BASS

Being a teen in the Deep South of the U.S. after hiphop broke was a dicey affair, especially if you were wanting to hear more and more of it. Throughout the first half of the 1980s, most hiphop from the upper east coast didn’t filter down south. I guess much of it proved too “urban” in its perspective to appeal to places that were at best only semi-urban. But electro-funk took in a big way early in the ‘80s, and had a lasting influence in the southeast. Kraftwerk’s “Numbers” and “Tour de France” got a lot airplay on the non-white radio stations. Stuff like Twilight 22’s “Electric Kingdom” and Egyptian Lover went over massively in clubs and on boom boxes. Some of it brought “that boom” that was popular with a certain demographic. But not enough of it. As Dave Tomkins wrote in his “Primer to Miami Bass” piece in The Wire many years ago, the sub-Mason-Dixon response to much of what was coming from up North was that it involved too many guys in spacesuits and not enough boom.

So the locals started making it for themselves, tweaking the music to their own tastes. And sure, originally the southern booty-bass sound did hail from Miami and parts thereabouts at first; but within a few years it was also coming out of Atlanta and Houston and elsewhere in the SE region. I can remember numerous nights of driving around on a Friday or Saturday night, punching across the radio dial until I found a program where a DJ was playing a weekend party set. Track after track of punchy bass that had my ass careening in the driver’s seat while I steered down thinly-travelled roads in the darkness. At some point me figuring I was listening to the 181st (then 182nd, & etc.) remake of “Planet Rock”, which I was just fine with.**

It was so prevalent, that one could be excused for thinking that that was what most of the hip-hop universe consisted of. So many years later I was a bit thrown when James Lavelle put together a compilation of early tracks by DJ Magic Mike, and I read reviewers writing things to the effect of: “Arrrrgh!! Why am I only now hearing this stuff?” Considering that it was so inescapable to me once-upon-a, I couldn't help being befuddled by finding out that the music was such a marginal & provincial thing.

EARLY '90s, PT. 1 - BLEEP & BASS:

Still a victim of geography at this point. A lot of early U.K. House/early Rave music didn’t make it my part of the country. College kids were I was at the time were in the thrall of lots of northern European “industrial dance”drek. What little early rave fare trickled my way seemed alright enough, because I welcomed the energy. Functional for the dance floor, but didn’t strike me as the sort of stuff I’d want to much time with outside of a club setting. Until a number of tracks popped up that really caught my attention, seemed to be going in a direction that really appealed to me. More bass, and a distinctive use thereof. And, just generally, electronic music starting to move in the direction of kicking its made-upcsounds every which way around inside the listeners head. Years later I would learn that all of these records had something in common; that being that they hailed from city of Sheffield and its surrounding area, and could be filed under the category of the “Bleeps and Bass” subgenre.

EARLY '90s, PT. 2 - HIT THE BREAKS

Around the same time, I was moslty immersing myself in what's not looked backed on as "midskool" hiphop. I also stumbled across a few tunes that excited me tremendously, because they signaled the entry of breakbeats into the rave-culture mix. But at the tim had no idea about “‘ardkore” being a thing, let alone a very divisive, scene-splitting thing across the water. Only that it sounded like something I’d been eagerly waiting for.

But we need to talk about a couple of Atlanta joints. First off...

True, Rob Base & E-Z Rock had had a big big hit using the Lyn Collins "Think" break on their mega-hit "It Takes Two" in 1988; and over the next several years a number of tunes by high-profile acts milked further hits with the same break. But this Atlanta act pitch-shifted it into higher, more punchier bpm territory in a way that must've given a lot of people ideas. The title of the track is sampled from a 2 Live Crew number, and shortly thereafter Luther Campbell & crew in down in Miami responded to 2 Hyped Bros's jawn by doing their own version of the above, speeding it up even more and adding heaps of club-flattening bass.

And then there's this...

B-side wins again, by way of Mantronix-style editing being flipped into full warpspeed. This time via a reissue of Atlanta's Success-N-Effect debut track "Roll It Up N___a", this time with a instrumental remix that had been outsourced to Miami DJs Charlie Solana and Felix Sama, who gave in a Mantronix-in-warpdrive overhaul, using a chopped-up sample of the Winstons' "Amen" break for the benefit of maximum punchiness. If Frankie's Bones's account is to be taken as vaguely factual, then he heard it at the time and started playing it in NYC, and from the audience reaction decided it was worth flipping to Carl Cox, who then took it to overseas connections, where it helped inspire the beginnings of UK breakbeat 'ardkore. Perhaps partly true, or maybe total bullshit, but most likely doesn't matter (except for those that might be looking to get all chauvanistically "nativist" about such stuff).

And admittedly, here's where things get tricky. Because it's the point at which the the symbiosis of bass and kick drum comes in, which could argue consists slippage or cheating on my part. But since the 808 was what got this particular nuum rolling, it totally counts by my (and plenty others') reckoning.

Whatever the case, both the "dew doo" [sic] and "amen" breaks will factor heavily in second (more Northern) part of this thing. But for now, that's the end of Part I.

* This is not bullshit. My wife thought it was, until she became an audiologist and put me into a testing booth. Not to gloat or brag, but -- even after years of my abusing my eardrums night after night spent blasting music through headphones, or a fair number of nights spent in clubs with the shittiest acoustics -- in the end my claims were fully vindicated by the test results.

** NOT ENTIRELY TRUE. Lyrics were another matter. Here there are some problems. Not the least of which was the annoying habit of the vocals consistently being placed far too high/frontally in the mix.

29 February 2016

Atmospheric Conditions

(Or: 'Bass Bits' Shootout Blahblah, Part Whatever -- the Post-punk/Proto-Goth Years)

Here's one I don't believe has turned up in any of Simon's bass polling: Barry Adamson.

Plenty of Magazine tracks where Adamson's bass all but takes the lead. If I recall, he once claimed he didn't learn how to play until the evening before the auditioning for Devoto's band. A bought a used bass guitar, but didn't have an amp, so he practiced by resting the neck of the guitar against the headboard of his bed, working out notes notes and riffs from the vibrations buzzing through the wood.

Perhaps Jah Wobble is an obvious -- if not a too-obvious -- nominee. Sure, Keith Levene's guitar tended to dominate much f the time, but Wobble kept things tethered. And according to a recent interview, he concurs with Adamson's method of self-instruction:

"'Where does bass dwell? It’s not in the bass. It’s in the interaction of things.' Learning to make drones by direct contact with a physical solid object 'actually taught me more,' he reflects, 'than having it powered into an amp. It's natural vibration.'"

Labels:

bass invaders,

communal riffing,

music,

post-punk

0

comments

21 February 2016

The Past is a Deleted Postal Code (Slight Return)

Emily Nussbaum writing about the throwback “rockist” angle of the new Scorsese-Jagger-et al TV venture, “Vinyl” in the latest New Yorker:

“'Vinyl,' in other words, is the Hard Rock Café: chaos for tourists. Still, if you squint, you can see what the creative team was going for — a deep dive into the muck of a long-lost Manhattan, all bets off, no safe places, no trigger warnings. For those who long for a pricklier age, the seventies have become something like an escapist fantasyland, and, honestly, I can see the appeal. When I watched 'Argo,' I got obsessed with how fun it looked to be a nineteen-seventies white guy. Tight avocado pants! Before AIDS, after the sexual revolution. Women in charge of the hors d'oeuvres, smoking in the office, and a strong mustache game. It makes sense that TV-makers have begun to explore this material, with ...and new projects due from Baz Luhrmann (South Bronx, disco, black and Latino) and David Simon (Times Square, porn, James Franco playing twins). Fingers crossed that a Lydia Lunch bio-pic starring Kristen Stewart is on the way. It'll be a relief to see shows use different lenses, in less corny genres, to capture those fading memories."Y’know when I first heard about this show, I figured it’d be better if it had been set in Los Angeles, seeing how the music industry was so heavily centered there at the time. With the West Coast cocaine-saturated premise being equally inspired by the writings of Nick Kent, supplemented by stuff from Barney Hoskyn’s Hotel California. But maybe not, because it might come across as too much of a retread of what Paul Thomas Anderson has already covered. And you’d have a hard time fitting punk into the story. And NYC had far more mobsters. And we know how much Scorsese likes mobsters.

In the 1980s, everyone thought that it was impossible that anybody would ever feel nostalgic for the 1970s. But then again, in 1995 not much of anyone could imagine the ‘80s being an era worth being nostalgic about.

But a number of historians have argued that -- in U.S. socio-political terms, at least -- the 1970s didn’t begin until as late as 1973. The above has me wondering when the decade can be said to have gotten underway, musically?* With Altamont? Or a year later, after the deaths of Hendrix and Joplin? Or with the delayed stateside arrival of the first three Black Sabb albums? Or when David Geffen started the Asylum label for the sake of giving Jackson Browne his first recording contract? Or when Dylan released the fuck-off to fans that was Self Portrait, and Greil Marcus supposedly responded by writing, “What is this shit?” Or maybe it’s at a much hazier point -- like whenever it was that major labels took the lesson from Woodstock that there was a huge amount of money to be made from the rawk biz, and devoted their resources to making it a Big Corporate Thing?

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

* Yes, I'm aware that all of the examples that follow are from the caucasoid end of the musical spectrum. On the r&b side, maybe it could be argued that the 1970s began when Norman Whitfield began steering the Motown sound into heavier, darker territory. Or when Curtis Mayfield left the Impressions. With jazz? Maybe when Creed Taylor set up the Kudu label and thereafter established the fuzak foundations for the type of drek that's now marketed as "Smooooth Jazz."

20 February 2016

Bass is the Place, II

If I had to pin it down to a single jazz piece, I’d have to go with John Coltrane’s “Africa.” Large ensemble, including two bassists, one of whom -- whether Reggie Workman or Art Davis -- lays down the pulse on top of which everyone else builds.

19 February 2016

Bass is the Place, I

(or: Bass & Infrastructure, Part Whatever)

Simon told me he expected me to weigh in with a some candidates from the jazz canon, like I did during the drummage shootout. Far be it from me to disoblidge.

But as I said at the outset, I more often than not tend to hear the bass in relation to interplay with the rhythm section as a whole. This is especially the case with jazz. There's plenty of great jazz bassists I could cite -- the obvious list that'd include Charles Mingus, Paul Chambers, Reggie Workman, Jimmy Garrison, Charlie Haden, Ron Carter, Richard Davis, Cecil McBee, etc. & etc. And I’d taxed to identify exceptional work (as evidenced by this-versus-that short solo) by any of the above that’d work for yootubage purposes.

So I think I’ll try this another way. That being: the role of bass in different ensembles hailing from different phases of a particular artist's career/evolution. The artist in question being Herbie Hancock.

Yeahyeah, maybe a bit of a cumbersome conceit, I know. Be that as it may, here goes...

After doing a brief live stint playing in Mongo Santamaria’s band, Hancock decided to do a "Latin" joint for his third LP as a frontman, a quartet outing that also included bassist Paul Chambers and percussionists Willie Bobo and Osvaldo "Chihuahua" Martinez. With the exception of one composition, Hancock completely ditches his usual heavily melodic style of playing; instead playing in an almost wholly percussive manner as he improvises and navigates his way in and around whatever the other three are cooking up (e.g., after the 4:20 mark in the clip above). As polyrhythmic patterns proliferate, shifting this way and that, the duty goes to Chambers to provide the pulse that threads everything together. In effect: Centering the isht.

One of Hancock’s contributions to the Blow-Up soundtrack. Supposedly the bassman this time around was Ron Carter, but this one sounds like it may’ve instead been handled by the sessions' guitarist Jim Hall. Whichever the case, chances are you’ll recognize it right away, seeing it was borrowed some years later Booty Collins when he provided the bass line for a certain very Huge International Dance Hit.

Early on Hancock had proven himself exceptionaly sharp in a couple of departments. Foremost was his ability to pen slick melodic hooks, the sort that put tunes like “Watermelon Man”, "Cantaloupe Island" and “Maiden Voyage” over with audiences and peers in a big way, scoring him a handful of very popular crossover hits. Second was the fact that he -- at the advice of his mentor, trumpter Donald Byrd -- got his publishing right in order from the outset; thus allowing him to collect all due royalties on the aforementioned hits. That money would serve him well by the early 1970s, when Hancock went into full plugged-in/dashiki-and-afro/Zen Buddhist mode with what became known as his so-called Mwandishi Sextet.

Comparisons to Miles’s electric material of these years are common, but there are major differences. Whereas Miles’s electro-fusion material was often cluttered, dense, and heavily scripted; Hancock & crew took a more open, organic, and spacious approach that made for a lot more breathing room between the musicians’ interplay and improvising. It was also a lot more “cosmic” (in a pysch-era/Sun Ra-ish sense) than much of Miles’s work. Aside from Hancock, the personnel for this period included Benny Maupin on reeds, trumpeter Eddie Henderson, trombonist Julian Priester, drummer Billy Hart, and Buster Williams on bass (with the later addition of one Dr. Pat Gleeson on synths). By the time they got around to recording their third and final album, Sextant, Hancock had all but fully ditched his acoustic piano, and Buster Williams’s bass pushed forward in the mix, weighting in with a buzzing, almost stoner-rock type heaviness. If that weren't enough, the bass parts are often multi-layered, usually with Hancock doubling it on the keyboard, and sometimes additionally fleshed with Maupin going low on the bass clarinet or Priester’s bass trombone.

As a musical experiment, the Mwandishi venture didn’t prove commercially viable. Audiences were reportedly enthusiastic, but limited; and the three albums the group recorded netted only modest sales. At which point all of Hancock’s royalties came in handy, him covering the losses and keeping the outfit going by paying band members and traveling expenses out of his own pocket before finally calling an end to the project.

With 1973’s Head Hunters, Hancock backed the whole electro-fusion enterprise up and tried it again -- this time with a more pop-minded approach in mind. And hey, did it ever prove lucrative. The funky New Orleans-style strut of the tune "Chameleon" became a massive hit, as well as a common staple in the repertoires of school marching bands across the country.

By this point he was working with bassist Paul Jackson, percussionists Bill Summers and Harvey Mason, and (once again) outre reedman Bennie Maupin. "Chameleon" is most often known in its abridged 7-inch version -- a version that shaves off a full 13 minutes of the original, largely paring the thing back to the tunes opening theme and vamps, in which Hancock carries the punchy tuba-like bass portions on an ARP Odyssey. It’s only in the song’s full version that you get the expansive middle section (roughly 7:32 - 13:00+ in the clip above), at which point Jackson takes over and helps open the groove up into more broad-vista terrain.

Hancock would record several more albums with the group in the years that followed. Jackson, Maupin and crew would record their own jazz-funk LP without Hancock, adding guitarist DeWayne "Blackbyrd" McKnight for 1975’s Survival of the Fittest; which would provide hiphop producers with a treasure trove of sample-worthy grooves in later decades.

17 February 2016

Red Dirt Bass

Memphis versus New Orleans edition, rock-steady style....

And hey, check the oh-so helpful annotation from an online (non-bass) guitar tabs for the Meters track:

As far as the regional preferences go in the classic soul department, I've always been shamelessly biased/provincial But to be geographically charitable, I'll throw this one out as easily being among the top five (if not top three) Most Icon Bass Lines of All Time:

Go back and compare the original Undisputed Truth version that had been done just months earlier. Whitfield & company definitely improved it the second time around, starting with scripting something catchier for the bass player.

And hey, check the oh-so helpful annotation from an online (non-bass) guitar tabs for the Meters track:

As far as the regional preferences go in the classic soul department, I've always been shamelessly biased/provincial But to be geographically charitable, I'll throw this one out as easily being among the top five (if not top three) Most Icon Bass Lines of All Time:

Go back and compare the original Undisputed Truth version that had been done just months earlier. Whitfield & company definitely improved it the second time around, starting with scripting something catchier for the bass player.

Bass Oddities

Thanks to Tina Weymouth, there were a number of early Talking Heads songs that were anchored in strong, prominent bass lines -- “Psycho Killer” and “Take Me to the River” being the first that come to mind. It looks like Simon concurs, since he's singled her out for attention. Yes, Fear of Music sports its fair share of tunes where Weymouth delivers. But “I Zimbra” in particular has never failed to amuse me over the years, mainly because of how the bass pattern alternately accents and punctuates the rhythm engine of the ensemble with an eccentric logic all its own.

And then there's this obscure items from the Chicago soul-jazz scene of the late 1960s...

Melvin Jackson had spent the previous several years playing with Eddie Harris (in fact, a few tunes on Funky Skull are reversionings of tracks he’d cut with Harris a year or two beforehand). Jackson had electrified his upright bass by hooking it up to a series of amps and effects boxes, much the same way that Harris had done with his own tenor saxophone. And to achieve a trippier effect, a number of songs on the album feature Jackson’s bass soaked down with liberal amounts of reverb and delay. The LP also features a lot of session players drawn from the ranks of Chicago's jazz scene of the late '60a (particularly those affiliated with the AACM) -- with the likes Lester and Byron Bowie, Roscoe Mitchell, Leo Smith, Jodie Christian, Phil Upchurch, Pete Cosey, and drummer Billy Hart helping put the whole thing over.

16 February 2016

Riddim Killers, II

(Bass & Infrastructure, Installment the Second - Mirrorball Edition)

I suppose it goes without saying that a strong bass line was central in the funk & disco eras, and there's a lot of tunes that make the cut. Far too many to include from the funk canon, so here's a few favorites of my own from the disco...

As 1978-9 rolled around, a lot of disco was becoming more and more generic, more pro-forma, part of which may've contributed to the inevitable backlash. Still, in those years there were still a few songs that featured hooky, poppin' bass lines. Here's a couple of other favorites, featuring (as above) another tune notable for being sampled by TCQ, and another jawn from the P&P label...

And then of course this big hit, in which the bass pretty much takes center stage:

In his first post on this topic, Simon mentions the Larry Graham-derived style of "slap" bass, which become so pervasive and overused by various post-punk and dance acts in the early 1980s. A Certain Ratio used it to good effect before things tipped past the point of maximum saturation:

Always deeply liked the way the bass glides over the surface of that latter tune. And of roughly the same vintage:

Another favorite bass line was from “Regiment”, from Byrne and Eno’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. Not complex, but it had a smoldering darkness to it. The duties are attributed to one session musician going by the name of (ugh) Michael “Busta Cherry” Jones, who -- if dodgey search-engine results are to be believed -- had around the time had brief stints playing with Parliament and Gang of Four. I suppose I wasn't the only one, judging from the number of times (like the above) it was sampled a decade or so later.

Riddim Killers, I

(or, Bass & Infrastructure, Installment the First)

And speaking of the Decades blogs, it looks like the time has come again; the time when one of the old inter-bloggal musical rifferama/shootout things gets underway. We’ve done riffs, intros, geetar solos, and drummige. And now it looks like Simon Reynolds has chosen this season’s topic -- bass!

Quite frankly, I had been waiting on this one some time ago. My own listening affinities have always tilted toward the low end. But still I think I might this one a bit challenging, given the fact that I a difficult time separating the bass out from its interlocking role in a given rhythm section as a whole.

To get the ball rolling, one of the first things that leaps to mind was prompted by my having recently seen the documentary The Wrecking Crew, which I deeply enjoyed. The thing was an endless parade of pop tunes I knew from my childhood in the early 1970s, lots of songs that were -- well before the advent of "Oldies” or "Classic Rock" radio formats -- still fairly ubiquitous at the time. What’s more, I was struck by the number of times I learned that specific parts of these tunes -- the instrumental hooks or portions that had first grabbed my ear, that had been my favorite part due to the way it made the tune exceptional or snappy, the parts that stood out and stuck with me -- were those parts executed by one or another of a network of (seldomly credited) studio musicians who played on countless West Coast sessions throughout the 1960s. Sometimes it was a guitar riff or what had been laid down by the drummer, but more frequently these tended to the bass parts. Once instance would be when Joe Osborn’s bass gallops ahead of the rest of the backing on the Fifth Dimension's version of "Let the Sunshine In." But most often it was the work of bassist Carol Kaye...

Soon as the film was over, I found myself picking through my record shelves, checking to see if any of the musicians in question turned up on certain favorite records. Sure enough, the first two I reached for featured Carol Kaye and "Wrecking Crew" drummer Earl Palmer, serving as the elegantly-played rhythmic backbone for the arrangements on David Axelrod's Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience LPs...

Serge Gainsbourg and arranger Jean-Claude Vannier cooked up a similar type atmosphere a few years later on Gainsbourg’s album Historie de Melody Nelson, complete with a similarly laid-back, funky grooves from the sessions’ bassist and drummer...

More to come, naturally.

05 February 2016

Because

Because I grew up in the 1970s. And because I later spent the better part of 20 years living in Chicago, almost all of it spent on the south side. In that part of town there was, among the homegrown population, a sort of perennial groove that was inarguably classic -- definitive. Once winter broke and people came outdoors, you could expect to hear certain spring soundtracking. Roy Ayers Ubiquity and early Kool & the Gang being big favorites. Early-to-mid '70s era Stevie Wonder and maybe the occasional Steely Dan joint. But guaranteed plenty of EW&F.

Earth Wind & Fire having started out as an entity very specific to the Chicago music that it evolved out of. In the group's early years, when its lineup was constantly shifting. In those days its membership encompassed musicians who'd played with local funksters The Pharaohs, as well as others who'd been under the mentorship of AACM multi-instrumentalist and former Sun Ra Arkestrateer Phil Cohran. (As evidence of that latter connection, check the larval EW&F's contributions to the Sweet Sweetbacks's Baadasssss Song OST.) And then once the band's lineup began to finally solidify, in stepped producer & arranger Charles Stepney to help steer them toward the limelight. Charles Stepney himself being a whole 'nother Chicago music story.

Labels:

music,

RIPs

0

comments

20 January 2016

Don't Talk to Sociologists

Mayo Thompson interviewed for BOMB magazine, speaking about divergent modes of creativity and the "waxen herring" of a 50-years-old conjectural musical project...

KC: Would you say you see Red Crayola as a product?

MT: Mike Kelley once told me that he was no democrat, but that we were going to have to have universal democracy before anything interesting could happen again. He was thinking about product, good product. Though he did not think art is redemptive, Mike was a utopian. He believed in progress. I don’t. And I don’t think anything is necessarily interesting. Something’s being interesting only serves those in whose interest it functions. Punk qua form wasn’t about making interesting music, rather about music as self-realization. Even poor punk was interesting, though, particularly if it sold. That’s what made the Crayola viable. Sales made it interesting in a broader sense. When we started we knew we couldn’t play up to the standards operative in those days but didn’t let that stop us. We made a virtue of what we could do that conventional musicians couldn’t do, and exploited that, with the idea of making them eat it thrown in. We were playing a theoretical endgame. We let the world know we couldn’t be bothered. You might say that was and to an extent remains The Red Crayola product. Our music expressed our aggressiveness, our attitude. When I heard The Beatles, Dylan, I thought, 'Fuck, cool. If that makes it, I can sing too.' The Sex Pistols had the same effect, giving people a sense that they might empower themselves. People discouraged me when I sang as a child, said, 'You can’t carry a tune in a bucket.' People still say that. Well, fuck it. I haven’t been trying to carry a tune. I’ve been essaying, expressing my interests in abstract terms, devil take the hindmost.

KC: So you do not consider the records that you have made to be works of some kind?

MT: If you mean artworks as such, no. I think of them as candidates for asymmetrical functional relations, open to interpretation.

KC: Having said that, would you refer to the band as a condition of a sort?

MT: Condition? You mean like, pneumonia? No.

To my lights, it just represents instrumental potential inasmuch as its value is tied to its use. Music has been instrumental to my being able to put ideas in play, having more fun than you’re supposed to, that sort of thing. I’m no purist, and don’t believe authenticity or sincerity save anything, not necessarily. The game is to make things that have to be dealt with on the terms they instantiate. My stuff doesn’t carry or necessarily suggest imperatives for others. It’s not well-formed in the scientific sense. In personal terms, it entails a measure of shame, because it would be nice if everybody were as fortunate as I in doing what they like.

Full interview here.

13 January 2016

Art Decade (Coda)

Some straggling, tangential thoughts; re legacy, canonization, etc....

Monday’s news eventually had me reaching for England Is Mine, Michael Bracewell’s lenghty rumination about the role of dandyism in shaping Anglo modernist cultural history. Flipping to the section where he addresses the Glam years of the early 1970s, in which the author frames Bowie and Roxy Music as staging some variety of sci-fi musical revue for the nuclear age:

“Hot on Bowie’s stacked heels were Roxy Music, who mingled science and artifice into a cabaret futura of decadent romance -- playing with nostalgia as Bowie played with the future. [...]

And yet Roxy Music and David Bowie, throughout the first half of the 1970s,...propounded notions of time travel that were heavily tinged with death, disorientation and decay. From Bowie’s ‘Five Years’, as an imagined response to the imminent end of the world, to Roxy Music’s ‘The Bob Medley’ (1972) in which the strains of an interior elegance are drowned out by gun-fire, the ultimate destination of their glamour was shaped by a romantic sense of mortality -- a plastic Keatsian ‘half in love with easeful death’. This strong sense of death beneath glamour...would be crucial to those post-punks who looked to the Glam age for their own aesthetic of death, dehumanization and Weimar decadence. As the sensual images of pin-up girls and swooning sirens on the covers of Roxy Music’s first four LPS hovered close to pornography, so too did their music move closer to the gloriously lurid, subverted by a arcane knowingness which crystallized their luxurious image into a sealed world of erotic melodrama: Edith Piaf meets Helmut Newton. Ferry -- ever the trend-setter -- would drop into German on the goose-stepping chorus line of ‘Lullaby’ (1974) to proclaim that the end of the world was nothing when one was stranded between love and art, thus setting into place, more or less, the entire agenda of New Romanticism.”

(At which point some readers might elect to supplant that “more or less” with a “for better or for worse.” No matter, Bracewell continues...)

“In terms of drama, David Bowie and Roxy Music turned pop concerts into rallies and Goth-Futurist theater, with the trashy rock-’n’-roll finding a natural home between the atmospheric, synthesized soliloquies of love and loss. Bowie singing ‘Sweet Thing’, as a lover lost in an urban future, could compete with Bryan Ferry singing ‘In Every Home a Heartache’ as a lover lost in Harrods; Roxy Music’s ‘A Song for Europe’, with its punning on the Bridge of Sighs, fitted nicely with Bowie’s double serenading of Jean Genet and Iggy Pop in ‘Jean Genie’. A whole new language had been invented for radical English pop, a kind of neo-Platonic plutonium plush, which was a world and a time away from the previous tyranny of American rockism over pop cool.”

Many of the Bowie obits and tributes that piled up on Monday and the following day featured the same component -- the blahblahblahing about the scope and extent of the artist’s influence on so much music that came afterward. Which prompted me to think about something I said in my prior post, the admission that I had gone nearly 25 years without listening to Bowie, without having much reason to think of him. Perhaps that was in some way testament to the degree of his cultural influence; that it was -- in certain aspects -- so pervasive in the pop industry (once again for better or worse) that it became all to easy to take that influence for granted -- it became such an inherent given, such an element of the environment that it like some sort of cultural wallpaper that was there when you moved into the premises, and long ago stopped noticing.

And the lazier tributes making it sound like Bowie was Glam rock, all but claiming that he’d invented it. Much like the lazy accounts of Pop Art that have it all beginning and ending with Andy Warhol. Like Warhol, Bowie was a somewhat late arrival on the Glam scene. And as such was initially dismissed by a few as a bandwagon-hopping opportunist.* But let’s be honest, were it not for him and Roxy Music, glam wouldn’t have ultimately amounted to much more than a footnote in the annals of pop music. If it had boiled down to the like of T. Rex, The Sweet, Slade and Gary Glitter, the whole thing would be remembered as little more than some Bubblegum 2.0 fad whose popularity was largely confined to the U.K.. (Next up, kids -- the Bay City Rollers!)

Which of course is the “authenticity” argument, the bulkiest and most unwieldy folder from the “rockism” file. Which I never fully understood, because the Authenticity party line was mostly a product of the late‘50s-early ‘60s folk movement, having only marginally spilled over into the ascendant rock scene in the years that followed.** Whatever the case, you can deem it as part of the cultural baggage from the 1960s that Bowie, Roxy, and other artists of the period decided could be readily done away with. (Relatedly, I saw this morning that Simon had posted something about the entrance of “meta” into the pop-music spectrum, via a 1980 interview with Brian Eno.)

And I realize that in siding with Bracewell’s argument, I place myself on one side of a dubious polemic adhered to by some people. That being the polemic that roughly goes: Sod all that high-minded, pretentious art-school hijackers’ alt-canon bullocks -- like a tosser who brings a book to a party, coming along and taking all the fun out of everything.

As far as Glam is concerned, I have no idea if either party Bowie or Ferry were privy to Sontag’s “Notes on Camp” essay; which is probably neither nor there because both parties they had something vaguely similar in mind. Ushering in the entrance of postmodern irony into the pop music arena, while showing notion of authenticity the door. Something pop-music artists and listeners have been mindful of ever since. All of which, of course, mostly has to do theater, presentation, image-making, artifice, public spectacle and the like, and -- one could argue -- nothing to do with music, per se. But hey, they don’t call it show biz for nothing.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

* One can imagine the sort of incredulity that broke out in the Leo Castelli stable when the gallerist decided to take Warhol on, with Lichenstein, Rosenquist et al. grumbling, “Who’s this interloping Johnny-come-lately? Oh, he already has a successful career...and a pile of cash to go with it? well, fuck him!”

** Which of course is the “authenticity” argument, the bulkiest and most unwieldy folder from the “rockism” file. Which I never fully understood, because the Authenticity party line was mostly a product of the late‘50s-early ‘60s folk movement, having only marginally spilled over into the ascendant rock scene in the years that followed. Admittedly, this would change in later years, by which point rock-related notions of authenticity were often tangled up with issues about economic class -- was such-and-such an artist from a true working-class background/”the streets”/whatever.

11 January 2016

Exit, Stage Left

Momus on this morning’s news, and the “theatrical timing” of Bowie’s passing:

"Apparently he’d had cancer for eighteen months. What a keeper of secrets, just as he was when he used to sneak in and out of Bromley bedsits, playing girls off against each other, giving everyone a different story! Sneaky David who lied to everybody because it really wasn’t any of our business! He even got Tony Visconti to lie about him being healthy and strong! I’d heard the cancer rumours, but I believed the lies. I preferred to, needed to: the lies were so much more palatable.

"But it wasn’t really 'unexpectedly'. His songs — the public statements that really matter — had all the while been spelling things out stark and clear to those of us willing to listen. I felt uncomfortable singing, in my Blackstar cover: 'Something happened on the day he died / Spirit rose a metre and stepped aside...' It was totally clear who 'he' was. And then came Lazarus, with 'Look up here, I’m in heaven...' And that video which has him disappearing into the wardrobe at the end. To Narnia, some said."

Of course there’ll be an avalanche of tributes hammered out and posted today and in the days to come, but I think I may stop reading there.

It’d be fair to say that Bowie was formative musical input during my early teenage years -- Station to Station being the first full album of his that I sank into, roughly about a year before the release of Scary Monsters. In the several years that followed, I did the backtracking and absorbed all of his back catalogue. But come my late teens and about 20-plus years of my adulthood, I paid him little attention -- never listened to his music (new or old), rarely had reason to even think of him.

What changed?, what prompted a revisitation after a long absence? I don’t know -- maybe it when younger critics, those who weren’t around back when Bowie was a big artistic entity -- began to appraise the man’s career at a more objective remove. Or maybe it was hearing Seu Jorge’s delicate versions of Bowie songs for the Life Aquatic soundtrack; hearing those songs in a more naked and humble form, stripped of their multipart arrangements and electric bombast, and realizing that underneath lay some very peculiar and at times lovely songwriting.

It prompted me to gradually revisit the early Bowie albums, curious to see how they’d strike me now that I’m much older and have the benefit of my own distance from the work’s period of origin. I found that my preferences hadn’t changed much over the years. The much-heralded, hit-making, high-concept Glam years -- good, but (as before) not among my favorites. Instead I found myself more deeply drawn to the fore-and-aft transitional phases -- particularly Hunky Dory and the “Berlin Years” material. The years when Bowie didn’t in advance know what direction he wanted to go, and was operating more by intuition and curiosity than by design.

But yes, back to the matter of timing. I’d spent the past few days noting the reviews of the new (and now final) album, Blackstar. Unanimously positive of the half dozen or so that I’d read. I couldn’t help but wonder if the verdicts of “his best album in decades” weren’t partly because of the element of unexpectedness of the project’s jazz-tinged experimentalism -- the surprising change of direction as proof-positive that the man still had a sense of artistic adventurism after so many years. Each accompanied with a checklist of reputed musical inspirations and influences on the project: Kendrick Lamar, Death Grips, and (perhaps mostly puzzling of all) Boards of Canada. None of which are, to my ears, apparent throughout the album. But a number of critics mention one possible inspiration that does make much more sense when I’d only heard excerpts from the first few of the Blackstar songs --- the music of Scott Walker. A bit ironic, that; considering Walker was a figure who has at the height of his pop fame at the time that David Jones took the stage-surname Bowie, spending the next several years floundering about in the U.K. pop market, before finally becoming the artist as he's now known and remembered.

And agin about that timing: I only got the album yesterday, giving it first spin around sundown. Yes, it’s frontloaded with the more experimental, more challenging tunes; but it ends with three songs that are -- by my reckoning -- among the most gorgeous things Bowie ever did. And the voice -- that distinctive throaty croon of his -- was undiminished by the years. By the time the album’s last song, “I Can’t Give Everything Away”, was in full sweep, my wife came into the room, practically clutching her heart. “This is really good,” she said to me. “Fucking hell. To think it was made by a man almost seventy years old. Maybe he really is an alien, after all.” Only then to awake to this morning’s news, which cast her comments -- as well as much of Blackstar's lyrics -- into an uncanny context. Fucking hell, indeed.

Labels:

music,

RIPs

0

comments

07 May 2015

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

WHAT

Headspillage, tangents, fragments & ruminative riffing. Guaranteed to sustain a low level of interest, intelligibility, or lucidity for most outside parties.

CONTACT:

greyhoos[at]gmail[dot]com

Elsewhere

(Contributing)

Esoterica

Effluvia

Edificial

- a456 ■

- Archiplanet Wiki ■

- Architectural Theory ■

- Brutalist Revival ■

- Critical Grounds ■

- deconcrete ■

- Diffusive Architectures ■

- Down with Utopia ■

- dpr-barcelona ■

- Fantastic Journal ■

- Iqbal Aalam ■

- Kosmograd ■

- Kostis Velonis ■

- Lebbeus Woods ■

- Life Without Buildings ■

- mammoth ■

- Measures Taken ■

- RNDRD ■

- Sit Down Man, You're a Bloody Tragedy ■

- SLAB ■

- Strange Harvest ■

- Subtopia ■

- The Charnel-House ■

- The Funambulist ■

- This City Called Earth ■

- Unhappy Hipsters ■

Etcetera

Ekphrasis

- 555 Enterprises ■

- A Scarlet Tracery ■

- Blissblog ■

- Dave Tompkins ■

- David Toop ■

- Devil, Can You Hear Me? ■

- Go Forth and Thrash ■

- History Is Made At Night ■

- Irk The Purists ■

- Nic Rombes ■

- nuits sans nuit ■

- Pere Lebrun ■

- Phil K ■

- Philip Sherburne ■

- Retromania ■

- The Fantastic Hope ■

- The Impostume ■

- Vague Terrain ■

Epistēmē

Eurythmia

- 20JFG ■

- Airport Through the Trees ■

- Blackest Ever Black ■

- Burning Ambulance ■

- Continuo ■

- Continuo's Docs ■

- Cows Are Just Food ■

- Cyclic Defrost ■

- Foxy Digitalis ■

- I Am the Real Kid Shirt ■

- Idiot's Guide to Dreaming ■

- Johnny Mugwump ■

- Kill Your Pet Puppy ■

- Lunar Atrium ■

- MNML SSGS ■

- Modifier ■

- Pontone ■

- Resident Advisor ■

- RockCritics.com

- Root Strata ■

- Sonic Truth ■

- The Liminal ■

- The Quietus ■

- Tiny Mix Tapes ■

- Waitakere Walks ■

- WFMU Beware of the Blog ■

Ectoplasm

Ephemera

- 50 Watts ■

- Architecture of Doom ■

- Bibliodyssey ■

- Breakfast in the Ruins ■

- But Does It Float ■

- Casual Research ■

- Cinebeats ■

- Critical Terrain ■

- D. Variations ■

- Daily Meh ■

- Dataisnature ■

- every other day ■

- Ffffound ■

- Hate the Future ■

- History of Our World ■

- Journey Round My Skull ■

- Landskipper ■

- lI — Il ■

- Lumpen Orientalism ■

- mrs. deane ■

- Nightmare Trails at Knifepoint ■

- no blah blah ■

- No Future Architects ■

- Open University ■

- Paleo-future ■

- Pietmondrian ■

- random index ■

- Smiling Faces Sometimes ■

- Today and Tomorrow ■

- twelve minute drum solo ■

- Utopia-Dystopia ■

- We Find Wildness ■

- XIII ■

- |-||-||| ■

Powered by Blogger.