(or: Twenty-five Tangents about Bowie in "Berlin")

Archival post, originally posted at ...And What Will Be Left

of Them?, April, 2011. It's a shame I can't re-post all of the

amusing responses that piled up in the comments section

1.

By all accounts, he had to get away from L.A. That much is a matter of undisputed public record. Some claim it was little more than a tax dodge, but others argue it was Bowie's attempt at breaking the maeslstrom of drugs and increasing psychosis that was consuming his life -- the obsession with Aleister Crowley, the traffic, escalating paranoia, the $500-per-diem cocaine habit supplemented by a diet of milk and peppers. Or maybe it was all of the above. But it had to start with leaving, getting out and getting away, extricating oneself from certain endangering circles, breaking with destructive habits and everything that fuels or enables them, and hopefully changing course and salvaging what's left of one's creative energies before it's too late. First to Switzerland, then -- eventually -- to Berlin. Leaving Los Angeles and all of its snares and poisonous associations behind. To hell with it all. Looking back, he would later say of Los Angeles, "The fucking place should be wiped off the face of the planet."

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.

No big surprise, really, that Bowie would inevitably wind up in Berlin. He'd been enthralled with Germany for some time -- fascinated, as some recent recorded comments and reputed gestures suggested, to a worrisome or problematic degree. He was deeply taken with its art and its music, with the decadent cabaret culture of the Weimar era, and -- more alarmingly -- with a certain sordid chapter of its 20th-century history.

But mainly it seemed like a good place to go to detox and collect one's wits. Bleak, depressed, somewhat coldly (and dingily) modern, furtively wrestling with its own history in the most repressed of ways, physically divided, socially and politically adrift in the throes of its Cold War limbo. That was the impression of the place as it existed at the time, anyway – the picture that the word "Berlin" commonly painted in a person's mind. A "come-down" city if ever there was one. You wander down a given city street, only to come to its sudden and abrupt end, the point of stoppage at which you find yourself facing the Wall. Some histories aren't so easily left behind, some histories leave harsh reminders.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.

It was Christopher Isherwood who put the idea of moving to Berlin into Bowie's head. Bowie had long been a fan of Isherwood, whose Goodbye to Berlin had undergone a recent revival in popularity from loosely providing the inspiration for the musical Cabaret. Attending the Los Angeles stop of the Station to Station tour in 1976, Isherwood and artist David Hockney had made their way backstage to converse with the singer afterward. The topic of Berlin came up. Isherwood would later claim that he tried to disabuse Bowie of the notion of going there, going so far as to dismiss the city as "boring." No matter, as it prompted Bowie to decide that a lack of distractions and some anonymity were what he needed to clear his head, and it wasn't much later that he started packing his bags.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.

Bowie wasn't the only one fascinated by Berlin in the 1970s. Far from it. A quick survey of the American cultural landscape revealed that a certain number of people in the U.S. shared a similar interest. Lou Reed's Berlin LP might've played some small part in the matter, with the way it sketched its setting in the gloomiest and starkest of tones. And there was also the popularity of the Broadway and film productions of Cabaret. Plus, the novels of Heinrich Böll and Günter Grass sold modestly well, with the films of Herzog and Wertmüller and Fassbinder and Wenders drawing crowds at the cinema in New York and reviews from urbane film critics.

As far as how the idea of Berlin was conceived and held in the American public imagination -- it represented something, must've served as some kind of metaphor. But a metaphor for what? Nobody ever said precisely, and perhaps nobody actually knew. Something having to do with trauma and unthinkable sins, with atonement and the weight of history, about rebuilding from the wreckage without looking back, of not being able to speak of the past, of living in a historical limbo. And about modernity. Because Berlin seemed deeply modern, but in a way that was as hard-won and enburdened as any form of modernity could be.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5.

"Amerika kennt keine Ruinen," art historian Horst Janson reputedly wrote in 1935. America knows no ruins. Ruins, as such, serve as a marker of history; of the past, of civilization having peaked and waned. In its sui generis exclusivity, America in the 20th century say itself as the embodiment of modernity. History was for the Old World, something that effected various elsewheres -- deeply European in its fatalism and determinism. To acknowledge it, to speak its name, meant playing the defeatist's card -- an admission of falling victim to causal forces beyond one's control. Never, never, never. America isn't shaped by history, America makes history. America knows no ruins because it is continually razing the grounds and building anew.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.

Unlike the projects that preceded it, Bowie's Young Americans blue-eyed soul schtick seemed like an aesthetic dead-end from the start -- conceptually limited, not the sort of thing one could build on, could take in any further direction. Transitioning into his European, world-wearied proto-New Romantic persona as the Thin White Duke the following year, Bowie would revisit the formula on Station to Station, albeit in a revamped, more dense and shadowy form.

Case in point, Station to Station's "Stay." Abetted by the chops of a couple of former members of Roy Ayers Ubiquity, the song showcases Carlos Alomar and Dennis Davis tucking deeply into the groove, getting louder and more open than they did on most of Ayers's recorded outings. "Stay," Bowie croons, although it sounds more like a suggestion than a plea. He sounds numb or placidly transfixed to the spot, while the band piles in a car, stomps the accelerator pedal, and screeches off toward their own destination, all but leaving the frontman in the dust. Stay? The singer was already in the act of grabbing his coat and heading toward the exit.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

|

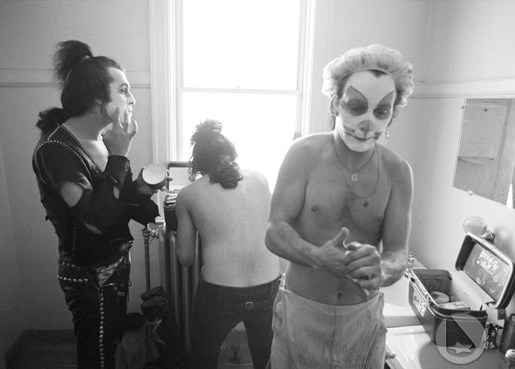

Left: Victoria Station, 1976. Right: Martin Kippenberger, Ich kann beim Besten Willen

kein Hakenkreuz entdecken ("I Can't for the Life of Me See a Swastika in This"), 1984.

|

7.

At Victoria Station in London, the camera shutter snaps and catches Bowie waving to fans, his arm in mid-sweep. The photo then runs in a number of tabloids, each claiming that the singer was seen giving the Nazi salute. Of course, that's just the tabloids being the tabloids. But it certainly didn't help that at about the same time he would make a remark in an interview about how Britain could really "benefit from a fascist leader." It was at that point that people started to wonder about the depth and the nature of the singer's Teutophilia, or if all that cocaine hadn't irreparably fucked his brain.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8.

In 1969, the artist Anselm Kiefer made a series of excursions across Europe. It was the earliest stage of his career, and the journey was the basis for a project -- a photographic travelogue titled Occupations. In each of the resulting photos, we see Kiefer at each of his stops giving the fascist salute.

There's something deeply, ironically comical about the series, as we see the artist as a lonely pathetic figure isolated within the frame, standing at attention with his arm held stiffly in the air. In Rome, at Arles and Montpellier, facing the ocean à la Friedrich's Wanderer Above the Misty Sea. An isolated and abject figure, a bathetic caricature of nationalist sentiment and imperial hubris -- ciphering away in empty and indifferent spaces, dwarfed by the surrounding landscape and architecture, repeating a delusional and ineffectual gesture ad absurdum, summoning the spectre of a lapsed and doomed history again and again and again. As if to drive the issue home with a visual pun, in one shot we see Kiefer in the same pose while standing in silhouette against the window in a trash-strewn apartment. Lebensraum. Of course.

All irony aside, the series still managed to piss off a lot of people at the time.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

9.

Albert Speer knew the value of history, and he also knew the importnace of ruins. During the 1930s, Speer was developing and promoting his own Ruinenwerttheorie ("Theory of Ruin Value") as the overarching principle for the imperial architecture of the Third Reich. The power of the state was to be exemplified in its architecture, he argued; architecture which would stand and sprawl boldly and proudly, endure for a millennium, and then look good in ruins as "relics of a great age." As the Reich's chief architect, Speer was most notably responsible for designing the Nuremberg Zeppelin Field and the German Pavilion for the 1937 World Exposition in Paris. But by dint of their grandiose and unrealistically ambitious character, most of Speer's projects never made it beyond the drawing-room stages. Among his grand, unrealized visions was that of overhauling the capital city of Berlin in a monumentally neoclassical fashion, in the process rechristening the new megalopolis Germania.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

10.

Reputedly, Bowie's interest in Berlin was mainly artistic in origin. As an aspiring painter, he'd always admired the German Expressionists. And in the middle of the 1970s, in the blur of cocaine and fame and things going off the rails, he was gravitating again to that initial interest in putting paint to canvas; devoting more time to doing so, if only as a means of (re)focusing his creative energies. Some stories have it that before he left for Berlin, he'd been discussing the possibility of doing a film called Wally -- a film based on the life of the Viennese proto-Expressionist artist Egon Schiele.

Nothing ever came of that project, so eventually he had to settle for being in Just a Gigolo instead. But looking at the cover of "Heroes", you might think Bowie was having a flashback to his early days as a street mime. If not that, then maybe he was running through a series of contrived and contorted poses reminiscent of Schiele's numerous self-portraits.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

11.

Common side effects of advanced cocaine use: Possible neurological and cerebrovascular effects, including but not limited to, subarachnoid haemorrhage, strokes of varying aetiologies, seizures, headache and sudden death. Symptoms might also include chest pains, hypertension, and psychiatric disturbances such as increased agitation, anxiety, depression, decreased dopaminergic signalling, psychosis, paranoia, acute and excessive cognitive distortions, erratic driving, writer's block.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

12.

A severe and minimal stage setting, Kraftwerk piped in over the p.a. before the performance, followed by Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel's surrealist short film Un Chien Andalous being screened above the stage. Bowie would claim that the idea for the stark black-and-white stage design was inspired by German Expressionist cinema, especially Metropolis and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. All of it signifying the "shock of the new" -- the adversarial tradition of modernism and the avant-garde in twentieth century art, complete with its aesthetic credo of relentless progress and innovation, of perpetual revolutions in artistic form and content.

The Third Reich, however, had no truck with the avant-garde. Goebbels (the failed novelist) had tried to argue with der Führer (the failed painter) about the nature of the regime's cultural policies, making the case that the ideas of a dynamic and forward-thinking society should be embodied in art and literature that was boldly and unapologetically modern. But Goebbels lost that argument, and was given the order to abolish all traces of the avant-garde -- to rid the culture of all art that Hitler deemed "degenerate" and "foreign" and poisonous to the constitution of a "pure" German culture. With that decree, all enclaves of modernist art, literature, and film in Germany were abruptly and sweepingly shut down, wiped out, or driven into exile.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .