I. DON'T GO BLAMING VASARI

Naturally, it all makes for a good story. I too once had a landlord I wanted to throw rocks at.

But there are plenty of pitfalls to wedding an evaluation of an artist’s work to their biography. One is the way in which this story quickly degenerates into cliché with each retelling. We know how these stories go: Jackson Pollock drunkenly raging and stumbling about while being dragged under by his own insecurities, Charlie Parker somehow radically changing the nature of music between heroin nods, Van Gogh cutting off his fucking ear. And something something something about their "demons." All good stuff for some bio-pic that’ll drum up moderate returns, but inevitably falling far short when it comes to explaining anything about what an artist accomplished. Nothing that adequately explains how their work was a “game changer,” or about the game that was changed, or why that game was possibly in need of changing, or about why any of this mattered in the first place. Nothing that explains the alleged greatness or “genius,” and certainly nothing about how said art may have been problematic in its time, but widely accepted and praised in the years after the artist’s death. Or, in the case of Caravaggio: the other way around.

II. ATTRIBUTION

Disputes over proper attribution are bound to coalescence around any artist who’s been dead for many centuries. As with so many other artists, so it’s been with Caravaggio. First there’s the array of sordid details – his scurrilous misdeeds, criminal offences, etcetera. About which the various accounts offer a fair amount of conflicting and contradictory info. Then there’s the matter of the man’s work itself, and which paintings can be rightfully credited to his hand, and the questions about which ones were done by students and imitators. The earliest accounts of Caravaggio’s life and work – brief though they might have been – were written by critics and contemporaries during or shortly after Caravaggio’s lifetime. Many of these dwell extensively on the artist’s temperament and exploits, offering a portrait of a reprobate, a shameless opportunist chasing after prestigious patrons, a habitual brawler and criminal offender, a denizen of the most undesirable layers of society. It’s possible that many of the earliest accounts were penned by critics who simply disliked the man, disliked his paintings, and were incredulous with the degree of artistic influence he had throughout the Baroque era.

Such might be the case with the overview offered by Giovanni Pietro Bellori. Published in his 1672 volume The Lives of Modern Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, Bellori’s account is largely devoted to cataloguing Caravaggio’s careerism and misbehavior than to discussing the artist’s work. But when Bellori turns his attention to Caravaggio’s paintings, the verdict is a harsh one. He conceded that Caravaggio was vastly influential on younger artists of his day, but dismisses the results as an art hinging on “novelty,” mere stylistic apeings of Caravaggio’s “facile manner.” Bellori liked the early phase of Caravaggio’s career, but – as more and more of each slips into swathes of darkness – much less so with the artist’s more renowned mature works. He seems especially troubled by Caravaggio’s disregard for working from sketches and classical models, his practice of working directly from observation. This break from traditional practice resulted, Bellori lamented, in an art in which “the antique has lost all authority.” With that in mind, Bellori summarizedW:

"...Many of the best elements of art were not in him; he possessed neither invention, nor decorum, nor design, nor any knowledge of the science of painting. The moment the model was taken away from his eyes, his hand and his imagination remained empty.”

Such was the consensus among a number of critics and patrons, both during the artist’s lifetime and over the next several centuries that followed. The gauge here was the art that had preceded the Baroque – the High Renaissance work of Da Vinci & co., and the convulsive vibrancy of the Mannerists who soon followed. The art of the previous era, the argument went, involved a process of extensive drawing, planning, development in the preparatory stages; a process in which subject matter was skillfully transformed – manipulated, idealized, refined, sublimated – by the artist’s imagination and intellect. By contrast, Caravaggio shrugged off established methods and classical models, opting instead to dumbly paint whatever was in front of him. Hence, he was little more than an impassive technician, “lacking inventiveness” – a mere imagist, but not a painter in the true, post-Renaissance sense of the word.

Slippage is also an issue here, as well. The account offered by André Félibien, is translated as asserting that Poussin – a friend and confidant of Félibien-- “could not bear Caravaggio and said that he had come into the world in order to destroy painting.” Another, more anecdotal, version is more specific; and contains a curious qualifier. On first viewing Caravaggio’s “Death of the Virgin,” Poussin is said to have cried out:

“I won’t look at it, it’s disgusting. The man was born to destroy the art of painting. Such a vulgar painting can only be the work of a vulgar man. The ugliness of his paintings will lead him to hell.”

The above has circulated broadly over the years, without any citation of its origin or source; and – as its histrionic flavor suggest – may be more the product of hearsay and apocrypha than fact. Mere semantic hair-splitting, perhaps; but the qualifying “the art of painting" might provide a key to what was at stake for Caravaggio’s detractors. Particularly when one bears in mind that the character and essence of art changes sharply from one epoch to another; and, even then, is still – if not always and forever – unstable, contested, open to debate.

But there’s something else, something that only adds to this confusion, and that is the painting above. Widely attributed to Poussin, it’s a study on paper bearing the title, “Death of the Virgin, After Caravaggio.” One assumes it to be an early work, done while Poussin was still a student; and, as with student works, was executed as a study – a technical training exercise, working from whatever models were available. What’s more, Poussin is said to have bean his career under the influence of Caravaggio, but eventually rejected that influence in favor of bright, rational, classically-referenced style of painting that was deeply indebted to Caravaggio’s contemporary and archrival, Annibale Carracci. It was this style of painting, Poussin reckoned, that set right the course of artistic evolution, which would serve as a panacea to the dreadful murk and muddle of the Caravaggisti.

IV. A LIKELY REASON FOR THE HEATEDNESS

If it seems like certain critics and cultural historians went after Caravaggio as if the fate of Western Civilization hung in balance of doing so, the it was because – in their minds, and as the sensibility of the times had it – there seemed to be that much at stake in the matter.*

V. THE FILTH AND THE FURY

Caravaggio trafficked in the “representation of vile things…filth and deformity.” It is this more than anything else that gets closest to the heart of Poussin’s alleged outcry. If Poussin’s remarks are apocryphal, and the words were put in his mouth well after-the-fact, it was probably because there was no shortage of critics in the eighteenth and nineteenth century who shared the same disparaging opinion of – or, more specifically, revulsion at – the art of Caravaggio. Chiefly among them was English Victorian and Romanticist grand esthete John Ruskin, who singled Caravaggio out for repeated abuse throughout the course of his writings. For Ruskin, Caravaggio was a “ruffian” and could be ranked highly among the “worshippers of the depraved;” his paintings epitomized a “re-enforcement of villainy” and the “horror and ugliness and filthiness of sin.” (Once again, the nature of painting – the what, how, and why of it – gets pegged on moral and philosophical imperatives.) Elsewhere Ruskin echoed the criticisms of Caravaggio’s contemporaries, labeling him a mere copyist who understood nothing of painting aside from its mechanical rudiments, and thus – along with Rubens and Rembrandt, et al. – guilty of foregoing Transcendancy and the Ideal for the sake fixating on fleshly, worldly, base material existence.

VI. ON UMBRAGE (THE TAKING AND THE USES THEREOF)

Caravaggio’s status would eventually be rehabbed in the early half of the twentieth century, at which point his canonical merits were re-secured. What, then, had been the problem – what about his work had been so egregious, had run so afoul of prevailing taste and hieratic artistic principals that it offended critics so deeply over the intervening three hundred years? As accounts suggest, Caravaggio’s “naturalism” seems to be have been at the heart of the matter. But the painter’s naturalism wasn’t confined to his rendering of human flesh and figures, or to the attention paid to mundane details. It also extended to bringing his subject matter into the present – providing viewers with recognizable figures, identifiably contemporary personages that looked as if they might’ve walked into the scene from the streets. It was this “from the streets” aspect that might has been the greatest cause of incredulity, to the degree that it merged the sacred with the profane. Overwhelmingly, Caravaggio’s paintings were of scenes derived from Classical antiquity or from Biblical tales (the latter having taken on even more cultural weight during the years of the Counter-Reformation). That being the case, it’s easy to imagine some viewers being appalled when these scenes were – as the story had it – peopled with and posed by a cast of urchins, prostitutes, paupers and assorted riff-raff. Caravaggio came from the lower tiers of society, and he saw no reason – given his limited means – to draw from that same population when he was in need of models. So much for idealization, nobility and grandeur.

But would that alone explain it? One wonders if it can all be chalked up to content-related matters; if the problems didn’t also involve issues of form, as well. Because, ultimately, the nature of Caravaggio’s overwhelming influence on his contemporaries was mostly in respect to visual style. It was the Caravaggio’s handling of light and darkness – his “tenebrism” – that would become the most widely-adopted aspect. As a pictorial device, this not only had the effect of boldly illuminating gritty and all-too-worldly detail; but of also dramatically shoving it forward toward the viewer. This effect could only be achieved by a means of visual staging, the sort that – by the artist’s hand – plunged various swathes and unreadable recesses of the scenes into unreadable darkness and shadow.**

In terms of composition, this amounts to severe theatrics. It also introduces a degree of abstraction – a breaking up of the image, raising obstacles of unintelligibility that frustrated the eye and the mind of the beholder. And perhaps troubled some minds, as well; the darkness and the unilluminated perhaps translating to a stubborn lack of disclosure, if not intolerable ambiguity – a manifestation of doubt, the unknowable, the inchoate, and thus perhaps of death itself. Perhaps.

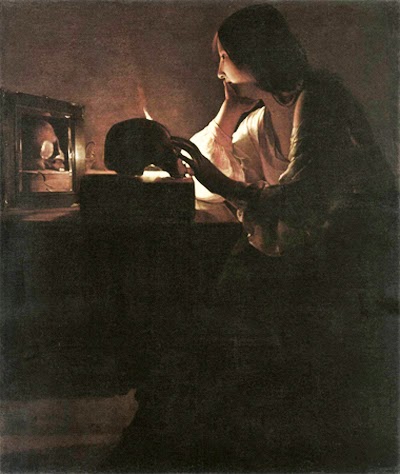

Whatever the case, Caravaggio’s influence would, to varying degrees, spread across Europe during the Baroque era, if not stylistically shape the era itself – influencing artists throughout Italy and across the Iberian peninsula, and as far north as the Dutch and Flemish regions. Among his most ardent apostles was the French painter Georges de la Tour. Like Caravaggio, De la Tour would frequently painted religious tales and themes, using models drawn from the local peasantry. Admittedly, his figures and settings are softer, more idealized and elegant than those of Caravaggio; and he overwhelming bypassed drama for the sake of tableaux that were calm, contemplative, almost the visual equivalent of silence. Yet at the same time, De la Tour took tenebrism to an extreme. He frequently opted for nocturnal scenes; scenes in which suggestions of volume, space, planarity are reduced to whatever happens to face the light source within the pictured scene, usually a single candle, torch, or lantern. Silhouettes, shadows, and darkness all but engulf the subjects and settings. What is known or knowable is limited to whatever falls within the confines of the flicker of a candle’s light. Everything else is only guesswork, speculation, and bumping up against things in the night.

* The Renaissance having marked marked a turnaround redemption of Western Civ from its derailments during the Middle Ages. Like the Baroque, the art of the Gothic had been written out of the canon until sometime roughly around the around the beginning of the 20th century; each having been classified as unfortunate relapses and evolutionary anomalies. In which case, one can't help but wonder if Caravaggio's paintings signified – in the centuries after they were painted – a form of regression, a return (visually, metaphorically) to the Dark Ages. Which seems fair enough when you consider that during his childhood, a considerable portion of Caravaggio's family and friends died from a resurgence of plague that swept many of Italy's urban centers.

** The darkness growing deeper and more predominant in Caravaggio’s later years, corresponding with the increasing morbidity of the themes depicted.

No comments:

Post a Comment